There is much to celebrate in Minouche Shafik’s argument that we need a new social contract[1], not least a title that uses the language of obligation and duty rather than employing the language of rights. This is even if she falls back, in her closing remarks, on answering her question of what it is that we owe to each, that it is “to muster the courage and sense of unity” that the Beveridge Report said was necessary for the “winning” of “freedom and want”. I was looking for more, and shouldn’t be too critical her effort at a rallying cry to round off the book when she has addressed a variety of policy measures, without being unduly prescriptive about their precise form, that would address “our interdependencies, provide minimum protections to all, share some risks collectively and ask everyone to contribute as much as they can for as long as they can….investing in people and building a new system of risk sharing to increase our overall well-being”.

Shafik’s underlying argument is that we need a new social contract to meet the needs and opportunities facing both individual society and global society in the 21st century, including those of an environment threatened by global warming and the degradation from human activity, of an ageing population, of an inequity between generations, and of the alienation of communities left as others have prospered that as consequence poses a threat the liberal democracy. She is qualified for this task by her personal history which includes an affluent childhood in Egypt that exposed her to third world poverty around her before her family emigrated to the USA, a career largely “in the trenches of policymaking” spanning international institutions and in the central government and central banking in the UK, and finally her current appointment as Director of the London School of Economics in 2017 where she launched a programme of research, ‘Beveridge 2.00’, to rethink the welfare state.

Having spent many years in healthcare and the application of health economics, I felt initially that her chapter on health was skated over too much. But this was before I reflected that the chapters outside my own area of knowledge were throwing me snippets of valuable information and new insights that left me with respect for the ambition within her 189 very readable pages (Thomas Piketty could learn a thing or two from Minouche Shafik!). Plenty of the examples in this book are familiar, such as the marshmallow test, but others cited, such as the evidence of the value of quite modest investment in early years intervention, such as weekly hour-long visits by Jamaican community health workers for 2 years to encourage mothers to interact and play with their children to develop cognitive and personality skills that 20 years later yielded 42% higher earnings than the control group.

Shafik sensibly avoids too many narrowly defined prescriptions, reflecting on data presented in the book that different countries have successful applied different policy solutions (for example in how they fund and organise healthcare) to achieve broadly similar outcomes (even if the one nation in the case of healthcare that doesn’t do this in a coherent way – the United States – ends up spending far more in aggregate, and in terms of public money, than everywhere else only to realise worse outcomes). However, the general thrust of her argument in each area of policy is clear.

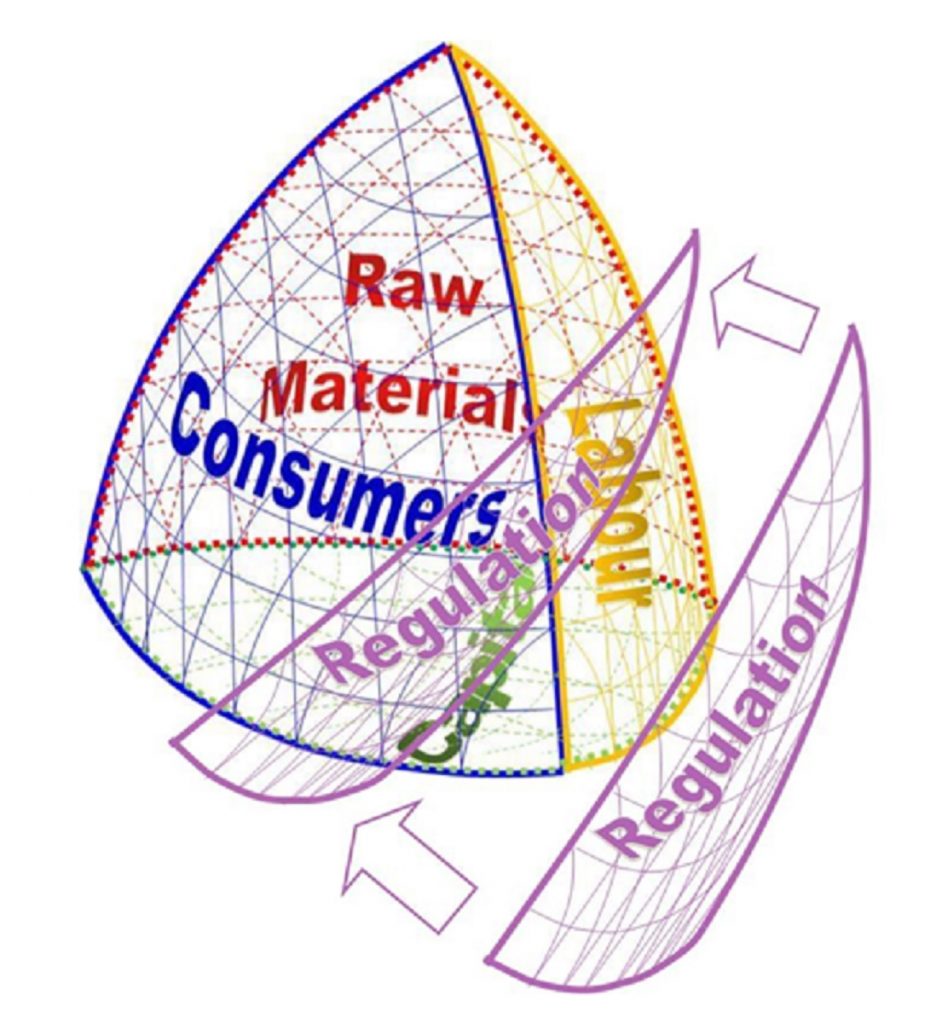

Shafik poses interesting questions around the intergenerational social contract. On one hand, younger generations are blessed with material well-being that the old generations could not have dreamt off. On the other hand, as David Willetts documented in the The Pinch[2], the millennials and generation Z have good reason to be aggrieved as they pay for the higher education and the home ownership enjoyed by their parents appears out of reach. Shafik recognises, in the emphasis that she places on investment in education in new social contract and various mechanisms for achieving this that she suggests. There is also the issue of the price that they and future generations will pay in terms of the environmental degradation resulting from the previous generations’ approach to achieving their wellbeing and economic growth. I am surprised at the complexity that she builds in to potential solutions to this when the solution should lie in regulation, a national income calculus that better reflects the value of the natural world that currently calculated GDP or national income, and environmentally based taxes that capture the externalities of industrial and agricultural activity that damages the environment.

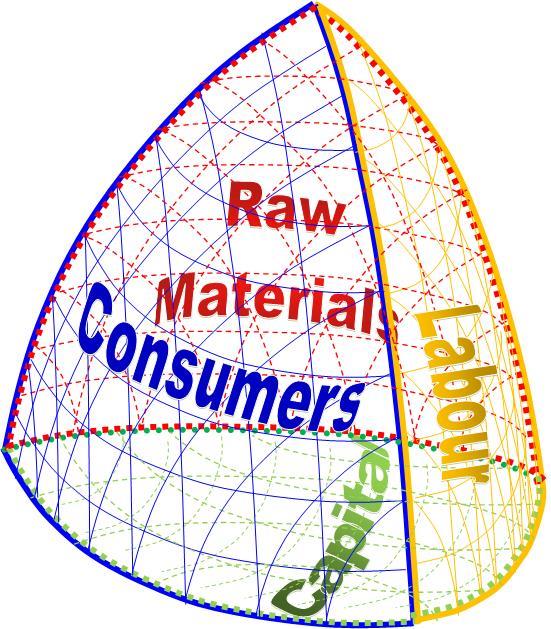

The book also gives rise to a set of interesting questions about what this means for businesses. Where do they sit within this narrative? There are important lessons for the people who sit at the heart of businesses, the “controlling minds” in terms what they can do, both in relation to their own workforces, customers and suppliers, in terms of contribution to a new social contract. For the business to thrive, and sustain itself in the long term, the core lesson is that it should be a player, alongside the individual citizen, in such a new social contract. Otherwise, its profitability and in due course its survival will be undermined by the very same pressures the Shafik describes threatening both individuals and liberal democracy.

I have a fear about one element in the approach Shafik takes to the need for a new social contract. This relates to what goes into the “increase in our overall well-being”. Some of the steam that is driving populism is increasing material inequality and the sense that communities are being “left behind”. Some of this populism is a function of identity politics, which may be whipped up by the perception that communities with other identities (often, but not exclusively, framed by other ethnicities or immigrant groups) are posing an economic threat or gain an advantage. But the perception may nothing to do with actual material wellbeing. Indeed, in the case of some of the 52% of the British population voting for Brexit, or the potential majority in Scotland for independence from the UK, this may be a desire to escape from or avoid the “other” despite the prospect that of material disadvantage. Some may be seduced by arguments that “getting back control” will leave them better off materially, but many others take the view that independence from Europe or the UK is more important than the economic benefit of remaining part of the whole. There is, at least at an abstract level, a link between the communitarian spirit in Shafik’s argument for a social contract “that addresses our interdependencies” and the desire to be part of a union, whether of states sharing a continent or Kingdoms sharing a small archipelago at the continent’s north western edge. Those same people who resist the membership of the country they occupy in a union of countries are also likely to be those most resistant to her arguments for a renewed social contract.

[1] Shafik, Minouche (2021). What We Owe Each Other: A New Social Contract. ISBN 978-1847926272.

[2] Willetts, David (2010). The Pinch: How the Baby Boomers Took Their Children’s Future – And Why They Should Give It Back. ISBN 978-1848872318.