I recently became Chair of the Legal Services Consumer Panel, an appointment by the Lord Chancellor and Minister of Justic created by the 2007 Legal Services Act with the brief to represent the consumer interest to the Legal Services Board and the regulators of the legal professions that it oversees. This article was published today on the LCSP website on the panel member’s blog page.

I’ve already been in post for two months, but only now publishing my first blog post. No sooner had my predecessor Sarah’s valedictory blog post been published but the general election was called, imposing restrictions on people in public office saying anything interesting. However, the delay has given me the opportunity to meet a selection of our stakeholders and start to get my head around the extensive and complex agenda facing the Legal Services Consumer Panel as it represents the consumer interest to the Legal Services Board.

I look forward to continuing the work undertaken by Sarah during her six years as chair. She will be a hard act to follow. I hope that LSCP can continue to make progress on the various fronts that she described in her final blog post: making the market work better for consumers, achieving greater transparency and improving access to justice. I am looking forward to LSCP publishing the report undertaken by Nottingham Trent University Law School suggesting ways in which the legal services regulators can give a greater focus on improving access to justice.

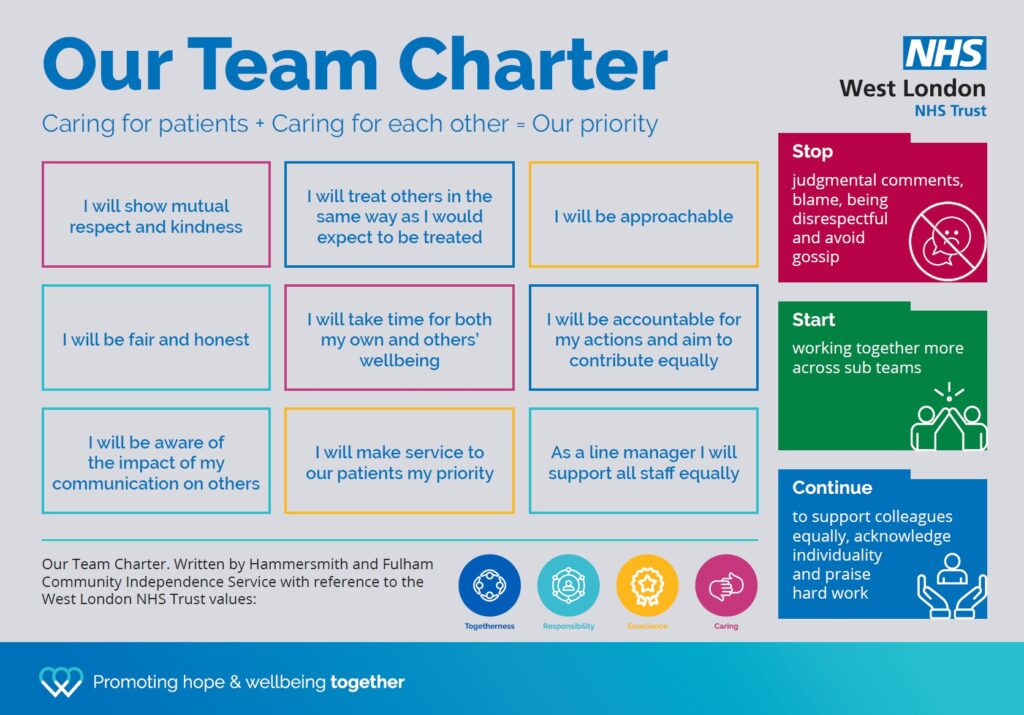

I come to this role with experience of professional regulation in healthcare (both as a former employer in the NHS and the private sector and as a panel chair for the Nursing and Midwifery Council) and in financial advisory services (chairing the Taxation Disciplinary Board and disciplinary panels for the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants). Common to professional services are the asymmetry of information and of self-confidence between the professional and the client, the difficulty for the customer when retaining the professional in assessing what constitutes good quality (above and beyond basic customer service) and consequently what represents good value for money. This is reinforced by the fact that, for most of us, the use of legal services is infrequent, increasing our unfamiliarity. In addition, our need for professional services is often at times of stress – for example, dealing with probate following bereavement, in dispute with an employer (or even before our professional regulator), buying or selling our home, or caught up in the criminal justice system.[1]

I am struck by the number and variety of issues currently affecting the legal services consumer that flow to the LSCP for consideration. It is not just those arising from relatively routine consultations coming to LSCP when the representative and regulatory organisations are considering changes, from our tracking the experience of the customers of legal services – particularly vulnerable groups – or from considering the impact of technology on the way that legal services are delivered. In addition to this bread-and-butter work is the need to address the existing themes highlighted by Sarah of promoting improved operation of the market, access to justice, and transparency. There are also a couple of major questions that have gained importance from recent developments.

The first is whether the regulatory regime adequately addresses moral compass, which should be at the heart of professional conduct and consequently central to protecting the interests of the legal services consumer. Evidence presented at the Post Office Horizon inquiry has raised very critical questions about the duties of lawyers. In a similar vein, as I look across to the legal professions from my role with the Taxation Disciplinary Board, I read last week former Clifford Chance partner and leading tax commentator Dan Neidle argue that “too many barristers are hiding behind the pretence they are neutral advisers when what they’re really doing is enabling quasi-criminal behaviour”[2]. The Post Office scandal and Dan Neidle’s allegations contribute to the case for constantly reminding professionals to maintain ethical standards and suggests, for example, that legal services regulators follow ICAEW which has increased emphasis on ethics within CPD for chartered accountants.

The second question is whether it is time to overhaul the regulatory regime established under the 2007 Act. With a new government elected with a mandate for “Change”, the legislative timetable is likely to be congested. However, I hope that the new Lord Chancellor recognises the case for the 2007 Act to be updated. This is reflected in my predecessor’s valedictory blog, in my initial round of meetings with stakeholders, and in work previously undertaken by the Legal Services Board and the Independent Review of Legal Services Regulation led by Professor Stephen Mayson. It is further reinforced by proposed redelegation of regulatory functions by CILex and change to the Legal Executive title. With my background in health regulation, where the regulatory and representative functions have been completely separated and the regulators generally much larger than those in legal services, I am struck by the complexity of the current arrangements, the lack of separation of most of the regulatory bodies from the representative organisations (notwithstanding the LSB’s Internal Governance Rules) and how small they are. I have been encouraged by the willingness of the leaders of the regulatory bodies to engage with LSCP’s consumer agenda but am concerned by the gap between aspiration and delivery. I note, for example, the difficulties they face – reflecting management stretch – co-ordinating their efforts and limited budgets to research and understand the needs of their consumers.

I recognise the risk of leaping to conclusions when only a few months into a new role. However, in regard to these two questions, I have heard nothing to suggest that ethical standards receive sufficient attention from the legal regulators or that the framework created under the 2007 Act provides the best approach to meeting the interests of the consumers and, indeed, the professionals in legal services.

[1] These features are not unique to engaging professional services: dealing with skilled tradespeople – whether for planned work or for a burst water pipe or dodgy boiler – can be pretty stressful too!

[2] A tax reform agenda for tomorrow’s Chancellor (taxpolicy.org.uk) https://taxpolicy.org.uk/2024/07/04/a-tax-reform-agenda-for-tomorrows-chancellor/?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email#1-hmrc-reform