My grandmother lived through two world wars and difficult times. She kept her politics, other than a general sense of fairness and distaste for injustice, close to herself. I remember it came as a surprise to me when she announced that she made her selection of fresh fruit (oranges if I recall) on the basis that they shouldn’t come from a nation with a pretty toxic regime and social system. Only a few years later, after discovering marketing during my Stanford MBA, I realised that it should not have been a surprise. It is an essential component of the Escondido Framework that our choices are informed by a wide range of considerations and trade-offs, albeit some may swamp others in their importance, and this affects what we buy.

I recently introduced an old friend who is researching impact investing by charity trustees to a former colleague who is chief executive of one of the largest group of family charitable trusts in the UK. The old friend is interested in the use of charity endowment to make mission-aligned investments rather than purely for financial yield. The former colleagues recounted how, as custody of the inherited wealth that the family invests in charitable giving passes from generation to generation, not only does the direction of the charitable giving shift, but also the attitude of the family members towards the non-financial impact of their investment decisions changes. This should be no surprise either, as impact investment strategies are only a short step beyond avoiding investing in industries that conflict with your charitable purposes (for example, as chair of the finance committee of Versus Arthritis, I had no hesitation in making the case that a health charity should avoid investing in industries like tobacco and alcohol whose businesses contributed to ill-health).

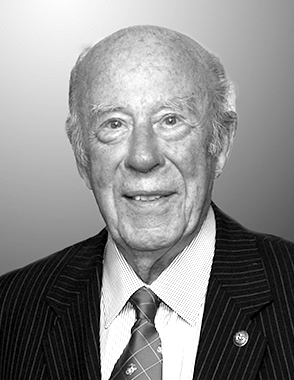

TPP’s Frank Hester

So what do I feel about the use by my family doctor (in common with all the GPs in west London and a large part of the NHS community services locally) using SystmOne, one of the most widely deployed electronic patient record systems in the UK? Most of my fellow patients have no idea that TPP (The Phoenix Partnership), which developed and operated SystmOne, was founded and apparently remains owned exclusively by Frank Hester. It was Frank Hester, the largest single donor to the Conservative Party, who has been alleged recently to have declared a few years ago at a company gathering that looking at Diane Abbott makes you “want to hate all black women” and that she “should be shot”. I don’t often have sympathy with Diane[1] who has very different political views to mine and has said some pretty daft and sometimes unpleasant things in the past. Comments of this type are unacceptable for many reasons and it reflects very badly on the company and its people that he felt able to make them.

I imagine that I will be holding my nose metaphorically when I next sit down in my GP’s consulting room as he or she updates my patient record with the details of my visit. If I was still chair at West London NHS Trust, where we were in the process of replacing a legacy electronic patient record system with SystmOne to provide for better interoperability with that used by our primary care partners, I doubt whether the knowledge that SystmOne was provided by a company headed up by someone with such views and that the profits were adding to his wealth would have changed my view of our IT strategy. Notwithstanding Mr Hester’s unpleasant views, the system produced by his company is the only one in town, or at least in my bit of London.

Whether things might have been different many years ago when TPP was starting out is moot. I imagine that Mr Hester was more cautious about what he said, how he said it and in whose hearing he said it, even in as recently as 1997. Certainly, I don’t recall being any less sensitive to boorish, racist and sexist language then, or my NHS colleagues being any less easily offended. But a generation on, and with the money in the bank and the software widely adopted, the customer (and ultimately their patients) has far less choice. Reflecting on this episode in Escondido Framework terms, the shape of the market interfaces have changed. How Frank Hester behaves, which has a bearing on how he does business, has almost certainly changed. Given the strength of his product with its customers and its established position against its competitors, he can (despite the widespread negative reaction his comments received) say unpleasant things without it affecting his business. For those of us who metaphorically are holding our noses, we have fewer degrees of freedom in our decision taking than we might have had many years ago if presented with a prospective supplier who acted in such a way (rather than exercising the restraint that was probably the case when Frank Hester was starting out with TPP in the late nineties).

[1] ……although I am entertained by the memory of serving with her as a fellow member of the Joint Academic Committee in the History Faculty at Cambridge University in 1974, when she (it can have been nobody else) described me in a student newspaper as “rather too obviously a Cambridge politician on the make” – wonderfully ironic given that she became the career politician whereas I made my escape from politics in the 1980s.