The FT has been carrying stories for the past two weeks about improving the quality of information provided by companies to their investors on the environmental impact of their activities and the sustainability of their businesses in the face of climate change. It may just be a coincidence, or it may be a conscious decision of the editorial board, but the Fashion Editor writes in “Life and the Arts” section of the Weekend FT on the same subject under the headline “Sustainable fashion? There’s no such thing”

On 5th November, Erkki Liikanen, Chair of the IFRS Foundation Trustees, delivered the keynote speech at the UNCTAD Intergovernmental Working Group of Experts on International Standards of Accounting and Reporting, introducing the Trustees’ Consultation Paper on Sustainability Reporting.

On 9th November, Rishi Sunak, Chancellor of the Exchequer, delivered a speech to the House of Commons on financial services. In the course of setting out his plans for supporting the City at the end of the transition period as the UK leaves the EU and plans to launch a Sovereign Green Bond, he declared:

“We’re announcing the UK’s intention to mandate climate disclosures by large companies and financial institutions across our economy, by 2025.

“Going further than recommended by the Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures.

“And the first G20 country to do so.

“We’re implementing a new ‘green taxonomy’, robustly classifying what we mean by ‘green’ to help firms and investors better understand the impact of their investments on the environment.”

On 10th November, the Financial Reporting Council launched its Statement on Non-Financial Reporting Frameworks, opening with the preamble:

“Climate change is one of the defining issues of our time and, by its nature, material to companies’ long-term success. Boards have a responsibility to consider their impact on the environment and the likely consequences of any business decisions in the long-term. Our 2020 review of climate-related considerations in corporate reporting and auditing found that boards and companies, auditors, professional associations, regulators and standard-setters need to do more.”

before recommending that companies should try to report “against the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures’ (TCFD) 11 recommended disclosures and, with reference to their sector, using the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) metrics” and setting out its own plans over the medium term to help “companies to achieve reporting under TCFD and SASB that meets the needs of investors”.

Today, 14th November, the FT’s fashion editor writes about the dilemmas facing those of her readers who are concerned about the impact of their purchasing decisions. She recognises that the best way to live a sustainable life is to buy less, but also that her readers want to find ways, while supplementing and refreshing their wardrobes, to plot their way through the “greenwash” claims of the fashion brands. Both these consumers and some of the brands themselves want clearer and more reliable accreditation of products that come from supply chains that are, if not truly environmentally friendly, at least less environmental unfriendly.

Following up the themes in this article, I found a great piece written by Whitney Bauck in Fashionista, in April last year:

“If you’re aware that there are ethical issues baked into making clothes but don’t have time to do in-depth supply chain research every time you need a new pair of socks, there’s a good chance you’ve thought at some point: ‘If only someone could just tell me for sure if this brand is ethical or not.’

“You wouldn’t be alone in that desire. In years of writing about both sustainability and ethics, it’s a sentiment I’ve heard from fashion consumers a lot. While many people want to be more conscious with their consumption, they also wish it were easier to tell which brands are truly being kind to people and planet.

“If you fall into that category, there’s good news and bad news. The bad news is that a one-size-fits-all ethical fashion certification will probably never exist, partly because not everyone agrees on what qualifies as “ethical.” Should that word refer to job creation in impoverished communities or animal welfare? Should it mean making clothes from organic materials or recycled synthetic ones? Not every ethical fashion fan has the same standards or priorities, and that will always make a one-size-fits-all approach to ethical fashion certification difficult.”

I wrote in a blog post four years ago about the benefits that the team I led at WH Smith believed would arise from developing and selling green stationery ranges. The issues described by Lauren Indvik in the FT are nothing new. We faced similar challenges both in terms of selecting products and in terms demonstrating to our customers that buying these products would better than buying alternatives.

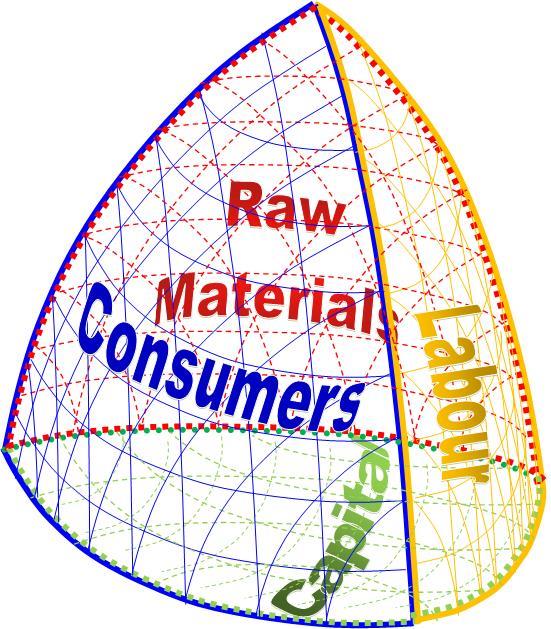

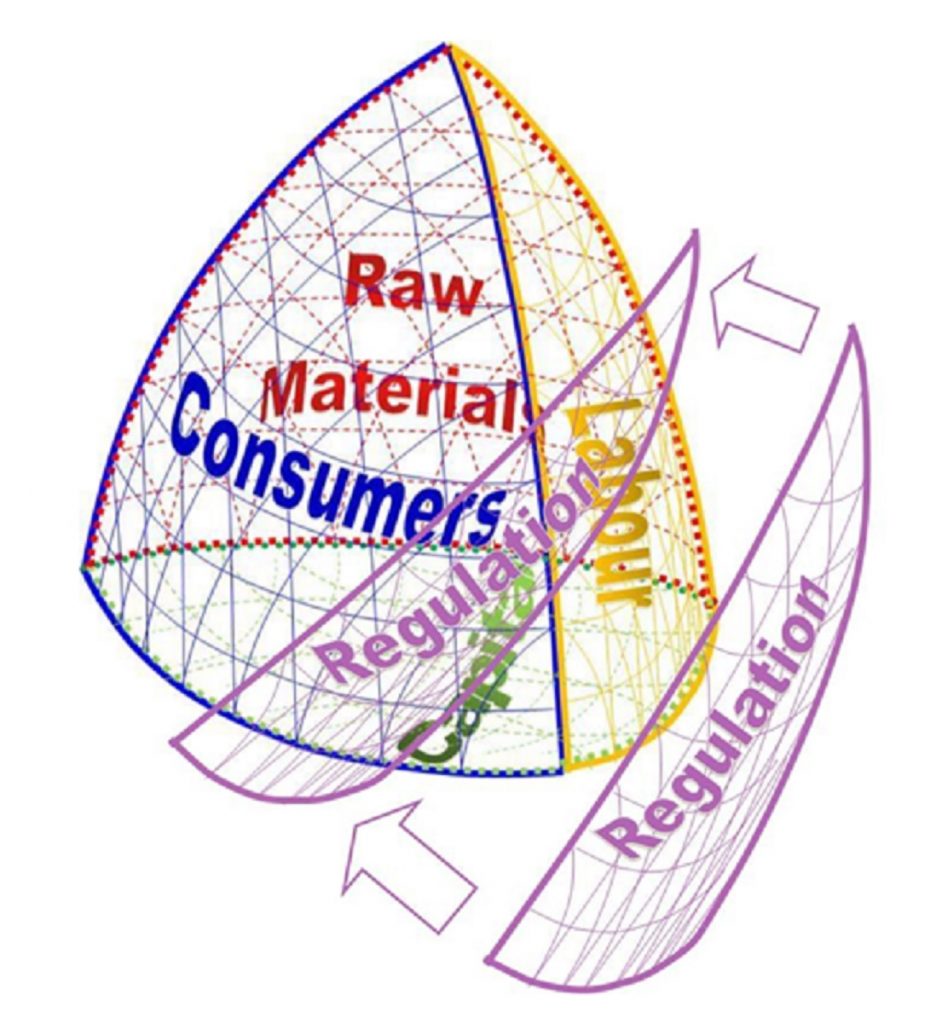

The challenges facing investors and consumers in taking environmental and other ethical considerations into account in what are otherwise commercial decisions are identical. Both investors and consumers want the best information, to put into the mix with the other things that influence their decisions – the complex trade-offs of exposure to multiple risks, timing, and return for the investor, or look, feel, comfort, durability, after sales support and cost* for the consumer.

The similarity between these challenges is evidence for the symmetry in all businesses – investors are customers for investment opportunities presented by the company, in the same way that consumers are customers for products and, indeed, that employees are customers for the jobs that companies provide. In an age when people – in their multiple roles as investors, consumers, and employees – want to invest in, buy from, and work for organisations that behave responsibly in relation to wider society and to the environment, they need reliable information to inform their decisions.

* and a host of other possible features depending on the product or service category