The classical model of the firm describes an entrepreneur who applies labour, with the assistance of capital, to convert raw materials into finished goods which are then sold to a customer. This particular version of the model describes a manufacturing business. Other versions of the classical model describe service businesses in which labour, with the assistance of capital, provide services to customers. Some of these services (eg restaurants) involve converting raw materials into finished goods (and consequently include some “manufacturing”) as well as providing a service (in this case, provision of a meal in a comfortable setting); others (eg distribution, wholesaling, retailing) may not involve any conversion of the goods bought in but involve providing them in the place, in the quantity, and at the time that the customer requires them); whilst others may involve the provision of services directly to the customer (eg hairdressing; professional advice) or to the property of the customer (repair and maintenance; insurance; security). Other versions of the model address primary and extractive industries (eg agriculture, fishing, mining), that combine labour and capital and apply them to natural resources, where any purchased materials are incidental to the goods sold to the customer in that they are enablers of the final output (fertiliser, energy, water) rather than combined into the final output.

Irrespective of which type of firm we are talking about, they all deal with suppliers and customers. With the exception of sole proprietors providing services that involve only their own labour and capital, they all deal with suppliers of one or more factors of production (eg labour and raw materials) and all deal with customers.

The simple classical model of the firm assumes that these transactions take place in markets where products have a single measure of utility or value to a customer and the quantity purchased will be a function of price. If the price falls, either more customers will come into the market to make a purchase, or individual existing customers will purchase more units. Similarly, the quantity of units of raw materials or labour purchased, or capital (whether capital goods or working capital) applied to the production process, will be a function of the price at which they can be purchased, since these prices will have an impact on how the production process is undertaken (ie lower prices may result in different a mix of inputs being used, or lower levels of efficiency or higher levels of waste being tolerated) and on the prices that need to be charged in the market to cover the costs of production, with a consequent impact on the quantities purchased.

However, the world is more complicated than this simple model. Few products are characterised by a single attribute against which the customer measures utility or value, and most are traded in markets in which there are substitutes – either a substitute product type (for example, if my purpose in purchasing the apple is a piece of fruit to eat as a dessert, I may substitute an apple for an orange) or a substitute in the form of the same product type but sold by a competitor.

The customer has to consider a number of attributes and make multiple trade-offs according to the mix of attributes delivered by the product (the choice between apples and oranges includes consideration of: flavour – which in itself has multiple dimensions; the tactile oral experience; degree of satiation; contribution towards liquid refreshment; energy content; ease of peeling; resilience to damage; product life) as well as the price. And price itself is not completely fungible, since there may be options around minimum quantities to be purchased; quantity discounts; payment methods and credit terms.

Firms purchasing inputs also consider multiple attributes. Labour is not undifferentiated: skills, experience, energy levels, behaviours, commitment, attitude, availability, reliability all vary. And different individuals respond differently to different elements of the explicit and implicit employment contract, including: working hours, length of contract, working environment, bonus and profit share, perks, security (both contractual and in relation to the employer’s business risk), corporate values, reputation of the employer, fit with of the appointment with the employee’s ambition. There are further considerations that will shape the decisions that prospective employees will consider about their employment, which the employer has to take into account when shaping its offer in the labour market, including proximity of housing, local education for children, the character of the neighbourhood, friendship circles. (I once had the challenge of explaining to a talented and gregarious young product manager who had grown up and was at the time living in Edinburgh why she should move to Swindon to work for me. Fortunately she interpreted that the fact that I put up with a gruelling 158 mile round trip commute from London rather than live in Swindon as evidence that the bright lights of the English capital were not too far away).

Although the market for capital deals essentially in a fungible element, money, the firm considers multiple attributes in its dealings here too. There is an extensive academic literature that considers the trade-offs between equity and debt, and the impact of the changes in the mix on a company’s cost of capital. In practical terms, a wide range of considerations come into play when a firm is looking for capital funds. Different sources of capital have a differing impact on the autonomy of management: this is not just the difference between raising equity and debt. Funding through selling equity to many small shareholders raises very different issues for management to raising money from a single shareholder, particularly if the single shareholder has a strategic interest in the conduct of the company. But different lenders may impose different restrictions on the autonomy of management, by way of covenants, or possibly by way of conversion rights in the event of a default. Different sources of capital may offer more flexibility than others, in terms of how the money is drawn down or repaid, with an impact on the total value of interest or dividend payments, and others will vary in terms of the requirement to make payments to a fixed timetable. The firm and its management may be able to reduce the cost paid for capital by offering by offering the provider of capital security over specific cash flows or assets, or access to them as a customer: this can range from a company’s founder offering his home as security for loan to his company through to a supplier of equipment providing capital by way of a leasing arrangement, or a supplier of products that the customer will process or resell also providing the necessary capital commitment and thereby securing its business with the firm (common practice in the ice cream and beverage industries, and also often an aspect of franchise operations).

In each one these markets the firm will make trade-offs between attributes, seeking the trade-off that is optimal given its particular circumstances. In some cases the trade-offs may be very clear-cut, with simple either/or choices, or a linear relationship between how much of attribute A is traded off against attribute B. However, with most of these trade-offs, as with other aspects of our lives, the relationship is not linear, and a little bit of A plus a little bit of B is preferable to a lot of only A or a lot of only B, a phenomenon described graphically in microeconomics by the “indifference curve” , (sometimes known as the Edgeworth curve[1] ).

These curves are in turn a reflection of the trade-offs made by the parties with who the firm conducts its transactions. The other parties also look seek an optimum mix of attributes when they consider they relations with firm, and with all the other firms they are dealing with. The investor, lender, or other supplier of capital (for example, someone extending credit to a customer) also trades off risk, security, absolute return, timescale, the value of the investment or loan as collateral, and possibly takes in account moral, ethical or political considerations. The consumer of the firm’s outputs will be taking into account the various potential product attributes described above. The employees and prospective employees will be concerned not only about the level of wages, but working hours, the wider terms of employment, job security, other benefits, and the various soft features, and trading the options provided by the firm with those available from other employers or from self-employment. And similarly, suppliers of goods and services to the firm will consider different attributes in the potential commercial relationship with the firm and with their other customers.

In most of these markets the firm is not dealing with a single indifference curve between a single pairs of attributes, but multiple attributes that can be imagined as a complex curved boundary surface, existing in as many dimensions as there are attributes. Furthermore, the firm is frequently dealing with many markets, not just the handful of markets described by the classical microeconomic model.

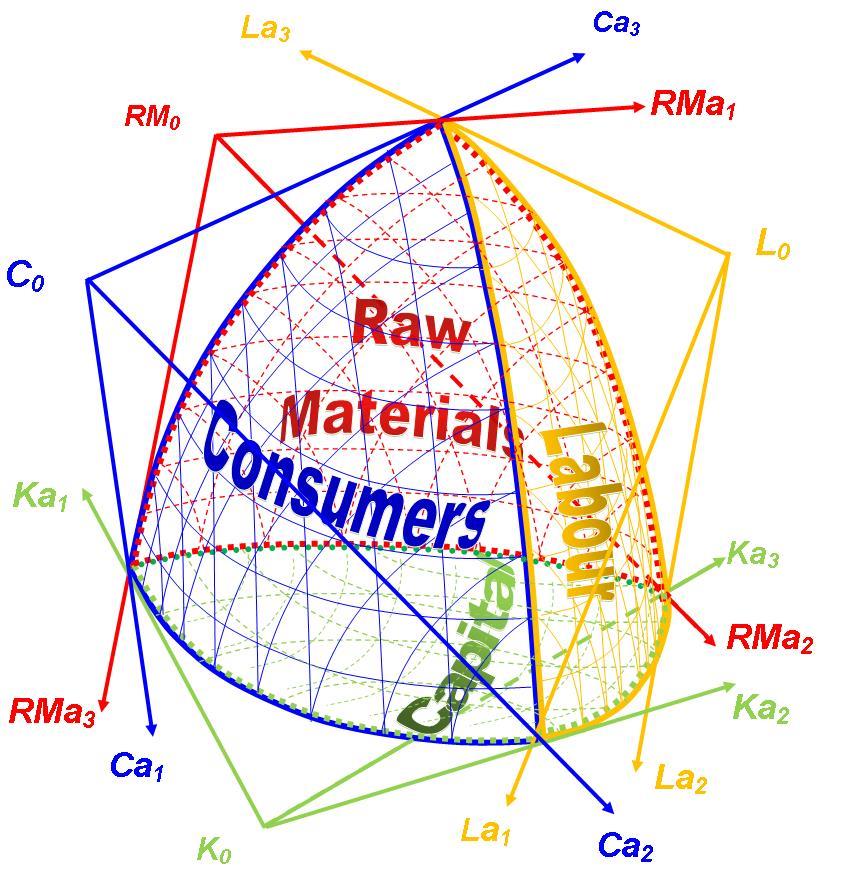

The human brain has difficulty handling more than three, or at most four, dimensions and our ability to project these visually is also severely limited. Reflecting these limitations, it is helpful to consider a simplified model of the firm on our way to understanding the greater complexity of the world that most firms face. In this context, we should start with a simple firm that produces a single class of product and deals with suppliers of capital, suppliers of labour, suppliers of raw materials, and with consumers. And, also to bring the model with the range of what can be readily described visually, it is helpful to limit the number of attributes that are considered in each market to three.

The image below, of a Reuleaux Tetrahedron, describes such a firm, interacting with four markets – capital, labour, raw materials, and consumers, with the potential boundary market boundary relationships – compound indifference curves – defined by three sets of attributes in each case. In the case of the market with the consumer, the attributes are described by the axes C0Ca1, C0Ca2, and C0Ca3, and the compound indifference curves across the axes fall on the boundary surface shown in blue. Similarly, the market relationships with the suppliers of capital are described by the boundary surface shown in green, reflecting the indifference points between the attributes described by the axes K0Ka1, K0Ka2 and K0Ka3; the market relationships with the suppliers of raw materials are described by the boundary surface shown in red, reflecting the indifference points between the attributes described by the axes RM0RMa1, RM0RMa2 and RM0RMa3 ;and the market relationships with labour are described by the boundary surface shown in yellow, reflecting the indifference points between the attributes described by the axes L0La1, L0La2 and L0La3.

This visualisation of the simple firm shows an empty space lying between the boundaries of the firm and its markets. This represents the available solution space to the firm, that is to say, its management have a choice about where at any time it may choose to operate. For many firms, the solution space is extremely constrained, under the paradigm of classical economics of perfect competition the solution space would collapse to a single point. But we live in a world of imperfect competition, at least in the short term, and the management of firms generally have some degree of discretion about where within the solution space they choose to operate. This is explored elsewhere in the Escondido Framework, for example, in discussion about the implications of the Framework for our understanding of ownership, about regulation, about corporate strategy, and about the capture by management of economic rent.

[1] Developed by Francis Ysidro Edgeworth and first published in “Mathematical Psychics: an Essay on the Application of Mathematics to the Moral Sciences,” 1881 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indifference_curve