Were the FT journalists consciously punning when they wrote this morning about Assured Guaranty (a US insurer reported to have more than $10 billion of exposure to some of the most indebted UK water utilities) “agreeing to provide liquidity facilities to Yorkshire Water”?

The long running problems with the financial management and governance of Britain’s water companies have come to a head with the crisis at Thames Water. The company has been at the heart of allegations about releasing sewage into water courses. The company is struggling with rising interest payments on $14 billion of debt. Sarah Bentley, chief executive has resigned. Along with the UK’s other water companies, who also face criticism for releasing untreated sewerage and collectively waste 20% through leaks of the water treated and ready for consumption, it faces public pressure for renationalisation. This sentiment is shared by Conservative Party voters who, according to a YouGov poll last year, are 58% in favour of a return to public ownership.

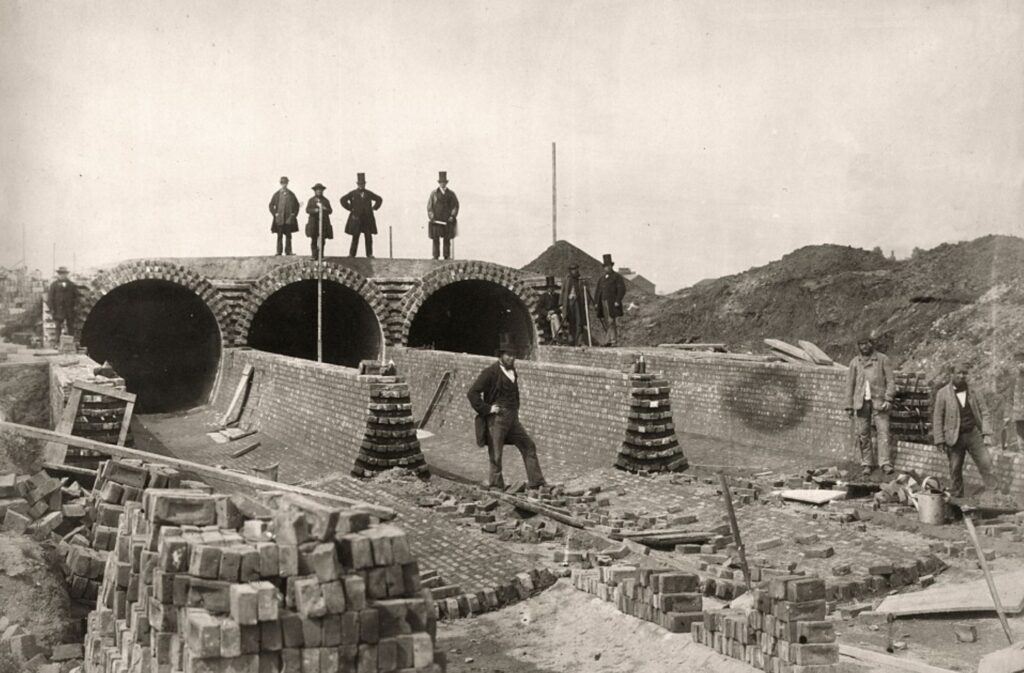

Before delving into the questions about governance, funding and risk bearing on the water industry, it is important to note the context. The water companies (and Thames Water in particular) operate a system that includes extensive very old and infrastructure (similar issues affect the UK’s railway system) that need maintaining, repairing and replacing, and face increasing demand from consumers and cope with the consequences of climate change – the paradoxical combination of longer periods of drought and increased frequency of incidences of torrential rain that exceeds the capacity of drains and sewers. This is well illustrated by the Thames Tideway Tunnel project, the £4.3 billion, 16 mile long “super sewer” nearing completion to replace Victorian sewerage system built under the direction of Sir Joseph Bazalgette between 1861 and 1875 and intended to reduce the number of “Combined Sewer Overflow” discharges into the Thames in London from an average of 60 a year to fewer than five.

But who is to pay, who should be running the show, and who should bear the risk when things go wrong? Ultimately the customer will pay, whether charges for domestic consumption are averaged out on a per household basis prior to water metering being rolled out or, as is now generally the case, based on the water you use (and is drained away on your behalf using water consumption as a proxy for sewerage generation)? (In a country with bountiful rainfall, the public struggle to understand why they should pay for something that falls from the sky, without understanding what is involved in getting potable water to them). When addressing the investment required for new reservoirs (noting that Portsmouth Water’s new reservoir in Havant will be the first in the past forty years despite at 21% growth in population) or schemes like the Thames Tideway Tunnel, capital needs to come from somewhere (whether from shareholder, lenders or government (either taxpayers or, more likely, investors in government debt, aka lenders) and then needs to be serviced until the cost can be recovered from the customer.

Since the regional water boards (responsible for both water supply and wastewater disposal – noting that thirteen smaller water supply only companies – generally former municipal businesses remain, albeit also now in private ownership), were privatised in 1989, they have geared up with substantial amounts of debt. Critics allege that this has released cash to pay over £60 billion in dividends to investors since privatisation, almost half the sum invested addressing the leaks and the sewer overflow discharges and increasing capacity. A further criticism of the companies is that the interest burden reduces the corporation tax paid by the water utilities, with the result that in 2021-2022 only South West Water reported a profit after tax, with Thames Water in the spotlight for losing £973 million.

Would nationalisation solve any of these problems? As a member of a sailing club that opened in 1979 on one of severally new reservoirs to the west of London, I am a beneficiary of the investment in water supply capacity by the nationalised water industry prior to 1980. I am not in a position to take a view on whether adequate maintenance or investment in distribution and disposal infrastructure took place prior to privatisation but I recall burst water mains and pollution of rivers and beaches in my childhood, so suspect that the nationalised industry underperformed on this count. The industry today has an economic regulator, the Water Services Regulation Authority, and is policed by the Environment Agency, both of whom have their critics. As Dieter Helm wrote in the Financial Times on 2nd July, the problems in the water industry demonstrate a prima facie case that the regulators have failed to use their powers adequately and that they should been given more teeth. But the problems identified do not make the case for replacing regulated privately owned companies with stronger governaance with a system of direct accountability for the management to ministers and civil servants in Whitehall, and financial accountability – including for access to capital for investment – to HM Treasury?