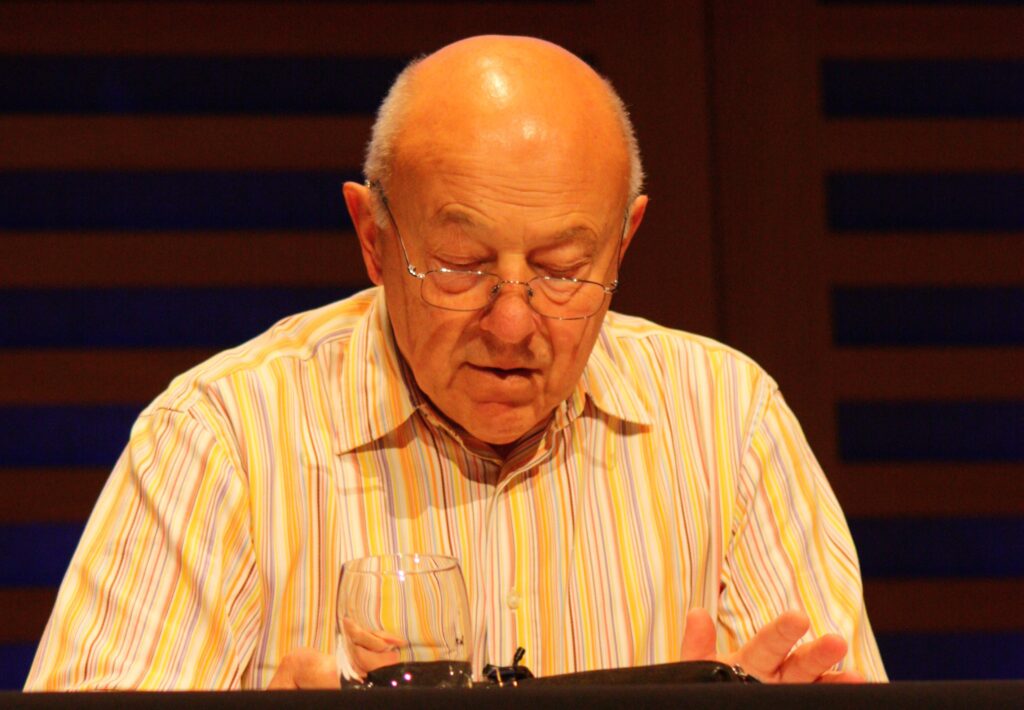

John Tusa is an eminent former broadcaster, managing director of the BBC World Service, and managing director of the Barbican Centre. He is a veteran of a variety of boards of cultural organisations and proud of being described as possessing “the heart of a luvvie and the mind of a suit”. He has written an account of his experience of governance that should be on the reading list of everyone either occupying or contemplating appointment to a board. His experience may be drawn from not-for-profit organisations in arts, broadcasting and education, but it is as applicable to boards in the private and public sectors as it is to the third sector. As he remarks in the introduction to “On Board”[1]:

“It is sometimes assumed that boards in the business world are totally different from those in the not-for-profit sector. This is far less true than might first appear. Both kinds of board choose their chair and chief executive, both decide how they appoint colleagues, how they sell to or serve their public, their customers or their audiences; both are responsible for brand, communication and reputation; both supervise the internal health of the organization. Of course, one deals with profit, the other does not. But while ‘not for profits’ are not businesses, they must be ‘business-like in the way s they manage their resources.”

While Tusa does not have direct experience of private sector boards himself, he has sat on boards with plenty of people with this experience, notably Kenneth Dayton, founder of the Target retail chain in the US and Tusa’s chair at American Public Radio, who pointed out to him that “governance in the not-for-profit sector is absolutely identical to governance in the for-profit sector”, besides which that it can also be a lot more complex.

Tusa builds his account of governance around his experience on the boards of the National Portrait Gallery[2], American Public Radio, English National Opera[3], the British Musuem, English National Opera, Wigmore Hall, the University of the Arts London and the Clore Leadership Programme, each of which merit a chapter reflecting interviews with fellow board members, executives and other stakeholders. Tantalisingly, he also alludes to other experiences, such as his time as President of Wolfson College, Cambridge, but without the same detail. Most of these organisations faced major challenges during his time with them, some potentially threatening to their existence. His accounts of how the boards weathered their storms and his candour about the mistakes made along the way are pulled together with a short section ending each chapter drawing out his reflections on what he learned from each experience and provide a rich seam of learning not only for people joining boards for the first time but also for those with many board appointments already on the CV.

This book should be read for the lessons Tusa draws out at the end of each chapter. Board members would do well to reflect on each, and whether they are applicable to their organisations. But “On Board” can also be read for more: it provides anyone who has observed the ups and downs of some of Britain’s leading cultural institutions of what went on around the board room table. As someone with strong ties to the Isle of Portland, I was suitably scandalised by the failure twenty years ago to use Portland Stone for the Great Court development at the British Museum. Tusa’s first career was as journalist and tells a good story, about this debacle and much more besides, as well providing a required text for chairs, directors and trustees.

[1] John Tusa, On Board (London: Bloomsbury 2020)

[2] His chair at NPG was Owen Chadwick, from whom I took my first lessons in chairing. Chadwick was Regius Professor of History at Cambridge University and a masterful chair of the faculty Joint Academic Committee, on which I sat as first year undergraduate (along with Diane Abbott, whose approach to faculty politics was considerably more radical than than the one she adopted later in her career as a leading member of the Labour Party in the House of Commons).

[3] I have a small gripe. John Tusa, having studied history at Cambridge, should know better than to suggest (in the context of ENO which, despite a catalogue of errors made by the board in the 1990s, managed to survive, an achievement that he observes “should not be underestimated”) that it was the French politician Talleyrand who said of his part in the French Revolution “I survived”. Far from just surviving, Talleyrand’s extraordinary achievement was to serve just about every government in France between 1780 and 1834, from the Ancien Regime, through every stage of the Revolution, the Napoleonic Empire, the Bourbon Restoration and the Orleanist “July Monarchy”. It was not Talleyrand, but Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès, usually known as the abbé Sieyès, a chief political theorist of the French Revolution, who is reputed to have said in answer to a question about what he did during The Terror of 1793-94: “J’ai vécu”