The Financial Times has published a flurry of articles and the occasional letter about ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance) investing recently.

For example, Geeta Aiyer, president of Boston Common Asset Management, was the subject of a profile on 29th August. This followed the success of Boston Common and other investors to secure the change of name of the Washington Red Skins American Football team by applying pressure on FedEx, the logistics company which sponsors the team’s stadium.

On 1st September the paper published an article about write-downs at BP and Shell in response to “scores of asset managers who have doggedly pressed the oil companies to set targets to reduce carbon emissions and recognise the financial impact climate change could have on their operations” . The article cites a number of leading fund managers who comment on the “explosion” in ESG investing. It also notes the role of regulation in changing perspectives, citing the requirement now placed on pension fund managers in the UK take sustainability issues into account in their investment decisions and the impact of the EU’s sustainable finance package which will, from March 2021, push asset managers to incorporate ESG risks in their decision making.

A day later, on 2nd September, the FT published an article by Chuku Umuna, former Labour business spokesman and now lead for ESG with Edelman, the public relations consultancy, arguing that “a company’s ability to manage ESG factors is widely viewed as a proxy for prudent risk management, and with good reason”, citing work by Société Générale on the impact of ESG-related controversies that found that “in two-thirds of cases a company’s stock experienced sustained underperformance, trailing peers over the course of the following two years.”

A few months earlier, on 9th July, Gillian Tett wrote an article that opened by observing that the major ESG indices in the US and in Asia had outperformed the equivalent all share indices in terms of the financial returns to shareholders and cited a report from BlackRock making the same case, not only in the past year but also in 2015/16 and in 2018. BlackRock put this down to two primary reasons: the momentum created by ESG investors pushing up prices as they seek to acquire these stock for their clients and beneficiaries; and the value to companies seeking to improve their ESG ratings the scrutiny to which they subject their supply chains and employee practices and the consequent benefits that arise to their businesses.

Does the Escondido Framework approach to understanding organisations help us understand what is going on?

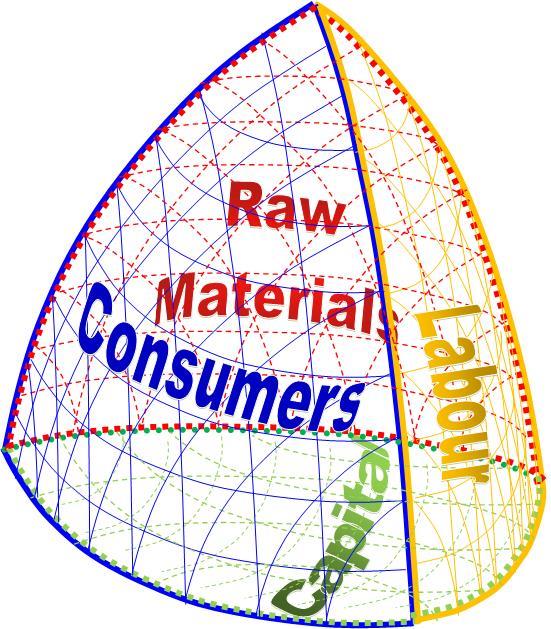

The Escondido Framework approach to looking at the firm is described in detail elsewhere. In essence, it explains that firms exist as a virtual space defined by their market interface with the suppliers of capital, labour, suppliers of goods and services, and customers, plus others whose needs may need to be satisfied, such as government or the wider community who implicitly or explicitly provide the firm with a license to do business. Their survival depends on creating value through the efficiency of their internal operations for there to be such a space. Where the firm places itself within the space will determine the distribution of economic rent to the stakeholders, how much may retained by the executive management, and how is available for reinvestment either in assets or long term relationships with one of more sets of stakeholders. As the market interfaces changes – through changes in supply and demand, competition, or the trade-offs made by the other parties to the markets place exchange – the virtual space (which can also be considered as the solution space available to the management team) may expand or contract (increasing or reducing the range of options, strategies and potential profitability available).

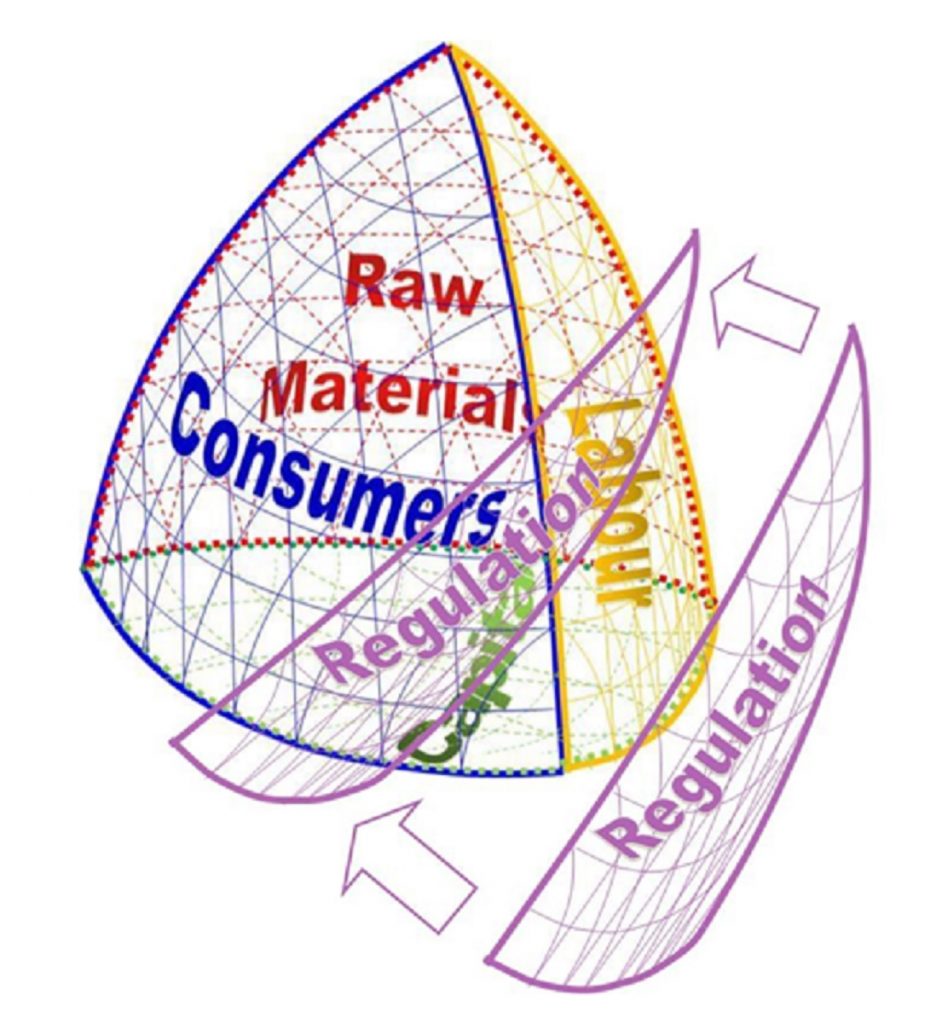

If a new external party intervenes, for example a government agency imposes regulation, the virtual space will be reduced correspondingly. Indeed, even the threat of regulation will have the effect of reducing the space as the firm is likely to take the view that it cannot afford to provoke the regulator.

So what is going on with ESG investment? ESG considerations have an impact on investment decisions in multiple ways.

Some investors will choose only to invest in businesses whose practices meet certain standards in terms of environmental and/or social responsibility and impact. When I was trustee of a large medical charity, we initially had a relatively limited list of sectors that we guided our fund managers to avoid, but progressively widened the list to avoid those whose products were implicated in contributing to the ill-health we working to address. Other charities have much wider exclusion lists, and many private individuals also choose to invest in ethical funds. Such investors are making an explicit trade-off between such potential increased returns as may be available from investing in companies (eg defence, tobacco) that don’t satisfy their ethical criteria.

Other investors decide to invest in ESG funds and businesses that meet ESG criteria because they believe that companies that with sound governance, ethical approaches to the communities in which they operate and setting high standards in their supply chains, and responsible approaches to the environment will ultimately deliver higher long term returns and be sustainable. Such investors may also take the view that these approaches also represent good business. Working in retail management as a merchandise director in the 1980s, I certainly took the view that being as environmentally responsible as possible was good business. I led a team that decided to adopt policies towards sourcing products from sustainable raw materials, reducing packaging, and developing “green” product ranges making extensive use of recycled materials on the basis that it was good for the business. It was good for our brand as it improved our standing with increasingly environmentally conscious customers. It was good for our sales, since people appeared keen to buy less environmentally harmful alternatives. It was also good for recruitment and retention of good staff, who seemed motivated (as I was) by working for a company that was trying to be environmentally responsible.

High standards of governance should also be appealing to investors, and the evidence is strong notwithstanding the mercurial successes of a few mavericks. As chair of a committee investing £200 million for the charity on which I was a trustee, I was attracted to Edinburgh based fund managers, Baillie Gifford, precisely because of the demands that it placed on the governance of their investee companies and its willingness to vote the shares it held for client like us to improve governance of the investee companies – and we were rewarded for our confidence in the approach by returns that consistently exceed the benchmarks for the fund.

If, as the flurry of FT articles suggests, there is an increasing appetite for ESG investing for whatever reason, the impact on companies is that (at least for the visually minded) the shape and precise orientation of their interface with the investment market will change reflecting either the trade-offs (in the case of the first type of investor described above) or the beliefs about the sustainability and long term returns (in the case of the second type of investor). The consequence of the appetite for ESG investing on companies is that those with business practices that align with the demands and expectations of ESG investors will face a slightly lower cost of capital and consequently increase the size of the solution space for the management teams when looking at their strategies.