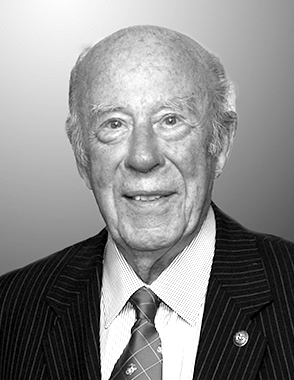

Over forty years ago, I attended a four session seminar at the Graduate School of Business at Stanford with George Schultz, then moonlighting as a part-time professor while serving as President of Bechtel Corporation. By that stage in his career he had already been a professor at MIT, dean of the Chicago University Graduate School of Business, and served in the US government as both Secretary of Labor and Secretary of the Treasury. Two years later, the Economist’s leading article gave a warm welcome to his appointment as Ronald Reagan’s second Secretary of State, after the disastrous Alexander Haig when the Cold War showed dangerous signs of overheating. The Economist reeled of a list of the world leaders with whom Schultz had built a close relationship over many years, which contributed the dialling down of threats to world peace during and following Schultz’s term of office.

Among the unexpected benefits of the Covid-19 pandemic has been the efforts of organisations to reach out to audiences with webcasts and webinars. My Stanford connections mean that I am on a mailing list for the Hoover Institution where Schultz remains, at age 99, a senior fellow, and to judge by the unmissable half hour session on Monday evening, a very active one.

I recall being put down in 1980 by Schultz when I made a case, the details of which I have long forgotten, for government intervention of some sort and he responded arguing against the approach I’d suggested and made the case for the use of economic, and specifically market levers. It was striking in this week’s interview how wide is the range of areas in which he now argues for intervention in relation to domestic policy, albeit still using economic levers, and international co-operation to address the range of threats to the future of our society, not least climate change and inequality.

As one of the architects of détente in the 1980s, and more recently an advocate for continued international collaboration (arguing for example that Britain should remain in the European Union), it was no surprise that he contrasted both the current deterioration in the relations between the superpowers and the America First foreign policy of the Trump administration with the post World War 2 settlement. He opened his talk by citing the vision both of those who gathered at Bretton Woods in July 1944 to establish a new international monetary and financial order and of the European leaders who met in Paris in 1951 to surrender sovereignty to establish the Europe Coal and Steel Community and thereby laid the foundations of the European Union.

He presented a depressing outlook for the world, given the scale of the climate change crisis and the apparent lack of reason in the approach of too many world leaders. However, I am not sure that I buy all the arguments that he made. In particular, he argued that the ageing of the populations of North America, Europe, China and the more developed countries of Asian (and given the need for population decline to reduce pressure on the environment and address global warming, the inevitability of an ageing of the global population), create the potential for an end to economic growth and squeeze on living standards, which seemed to take little account of the potential for extending productive lives.

But, however interesting his view of the global outlook and whatever the pleasure for me of this trip down memory lane, what justifies including an account of Schultz’s webinar in this blog? The “takeaway” is his account of the importance of personal relationships and human interaction. It is clear from his anecdotes that his ability to rub along with people made a huge difference to the resolution of problems in the United States’ relationship with the rest of the world both when he was Treasury Secretary and, most critically, Secretary of State. The Economist was right in 1982 to hail the appointment of this massively networked figure. Interpersonal skills are important to the management of the interface between organisations, right up to the size of superpowers. They are also critical to the effectiveness of internal operations. In answer to a question about the dysfunctionality of US government and politics today, he observed that the key figures in both executive and legislative branches all lived in Washington for most of the year, and he would regularly meet over dinner with congressmen from both sides of the aisle, in contrast to the situation today. A glimpse perhaps of the Dark Matter that makes organisations work?

My recollection from our encounters in 1980 is of a solidly build man in late middle age (at least from the perspective of a 24 year old) with a gravelly baritone, a contrast with the smaller man of today with a voice pitched an octave higher. There is only so much we can do to hold back physical ageing, but it is inspiring to see that there is every reason for remaining engaged and committed to public debate. Schultz’s recipe for a long and active life was revealed in answer to the final question addressed to him: “Don’t stop working on the things that interest you.” There is no sign that George Schultz intends stopping soon.