The Boston Consulting Group’s latest BCG Perspectives brings a TED talk from one of its partners, Martin Reeves, titled “How to build a business that last 100 years”. His thesis is that we should look to lessons from biology to create lasting businesses. He links the failure of businesses to survive – pointing out that the average US public company has a life of only thirty years and probability that any public US company will still be around in five years’ time is only 32% – to a “collapse of the corporate immune system”.

He explains that human immune system, and indeed all successful biological systems from forests to fisheries, and indeed such long lasting social systems as the Roman Empire and the Catholic Church, display six characteristics:

- redundancy (“millions of copies of each component — leukocytes, white blood cells – a massive buffer against the unexpected”),

- diversity (“not just leukocytes but B cells, T cells, natural killer cells, antibodies”),

- modularity (“the surface barrier of the human skin….the very rapidly reacting innate immune system…..the highly targeted adaptive immune system……if one system fails, another can take over”),

- adaptivity (“able to actually develop targeted antibodies to threats that it’s never even met before”),

- prudence (“detecting and reacting to every tiny threat, and furthermore, remembering every previous threat, in case they are ever encountered again”),

- embeddedness (“in the larger system of the human body, and it works in complete harmony with that system, to create this unprecedented level of biological protection…… if one system fails, another can take over, creating a virtually foolproof system”).

He explains that along with and as a consequence of these characteristics, biological systems are complex and can seem inefficient, in contrast to the instincts of most managers and what is taught in business schools and preached by consultants.

Reeves continues by applying these lessons to examples of corporate failure. His first is the tragic loss of independence of Kongō Gumi, builder of Japanese temples for 1,428 years and managed by members of a single family until it forgot the principle of prudence, borrowed heavily to finance real estate purchases in the 1980s and was finally liquidated in 2006 and its assets sold to a large construction company.

Shitennoji Temple, built by Kongō Gumi (578-2006)

He then contrasts the collapse of Kodak with the successful adaptation of Fujifilm, which used its capabilities in chemistry, material science and optics to allow it to diversify into sectors outside photographic film, surviving “because it applied the principles of prudence, diversity and adaptation”. He also cites the success of Toyota in surviving a devastating fire in the only plant which supplied it with valves for car-braking systems. He describes Toyota’s ability to work collaboratively with its suppliers to repurpose production as an application of “the principles of modularity of its supply network, embeddedness in an integrated system and the functional redundancy”.

I am sure that there is something in Reeves’ argument, but some of it is contrived and overall it would be more compelling if some of the example illustrated his six principles more comprehensively, rather than only illustrating one or two.

Certainly Kongō Gumi’s demise reflects a lack of prudence – but the most extraordinary aspect of the story is that it had survived for as long it did, which may reflect the lack of underlying change in the Japanese temple market over almost a millennium and a half. To quote Business Week’s report on its demise:

“To sum up the lessons of Kongo Gumi’s long tenure and ultimate failure: Pick a stable industry and create flexible succession policies. To avoid a similar demise, evolve as business conditions require, but don’t get carried away with temporary enthusiasms and sacrifice financial stability for what looks like an opportunity. These lessons are somewhat contradictory and paradoxical, to be sure. But if sustained success came easy, then all family businesses would have a 1,428-year run.”

The Fujifilm example illustrates the benefit of diversity in a portfolio, but says nothing about the photographic film enterprise itself. Fujifilm’s survival represents the success of a corporate parent in managing a portfolio (ie the business of managing businesses), protecting the interests of a top management group, but says nothing about the business unit that brought together employees who worked in factories producing film, the customers that constituted the channel to the camera owner, or its suppliers. Essentially, as technology moved on, the “virtual space” between the various market interfaces disappeared and nothing that could be done to protect this enterprise. Its corporate shareholder – the Fujifilm group company – had elected to redeploy the cash flow into other businesses because the ultimate shareholders were either not in a position to, or chose not to, intervene.

Toyota is celebrated for how it manages itself supply chain and the nature of these relationships, but the fact of its ability to bring brake valve production on-line quickly illustrates only three, and possibly only two (given that it explicitly did not have redundancy in its supply chain given that it maintained a single source for these components), of Reeves’ biological system characteristics.

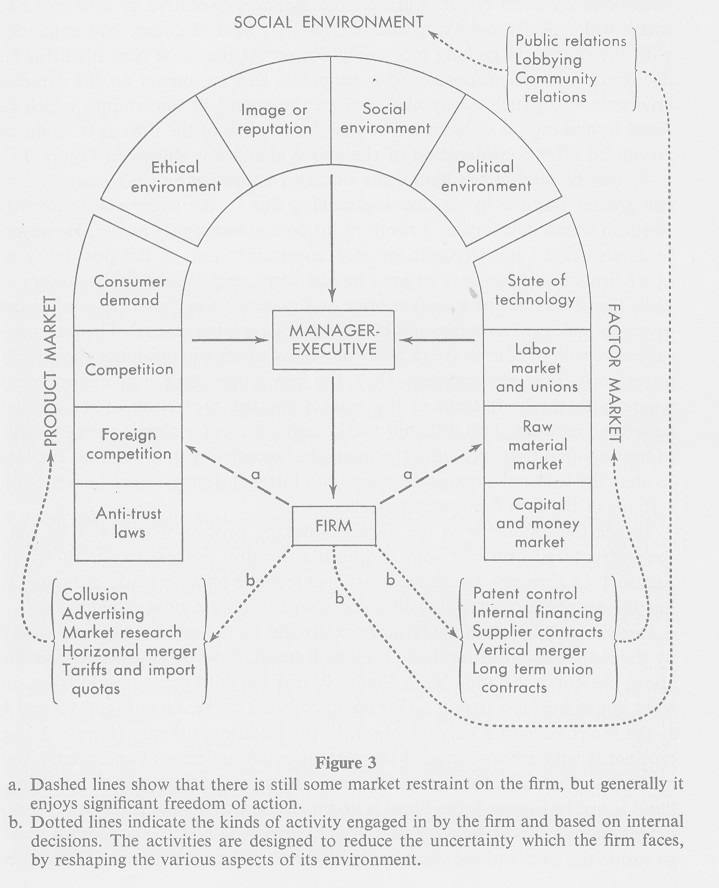

Considering Reeves’ argument and his examples and relating them to the Escondido Framework model of the firm, I certainly concur with three of his principles: adaptivity, prudence and embeddedness. I get redundancy, although not quite as he defines it, but at least that bit of spare capacity, underused resource, or financial headroom. But the need for and appropriateness of modularity and diversity must depend on the circumstances, and sometimes are in conflict.