Rousseau observed that “Man is born free but everywhere is in chains”. Many people in business, politics and media talk about markets in a similar way, as though “free markets” are the natural state and desirable order and any intervention by an agency of the state or collective popular action is represents an undesirable fettering of enterprise.

Economists since Adam Smith have recognised that markets can fail and may need to be subject to intervention. Even figures as inspiring to simplistic supporters of free markets as Milton Friedman recognise that there are proper roles for the state where markets fail.

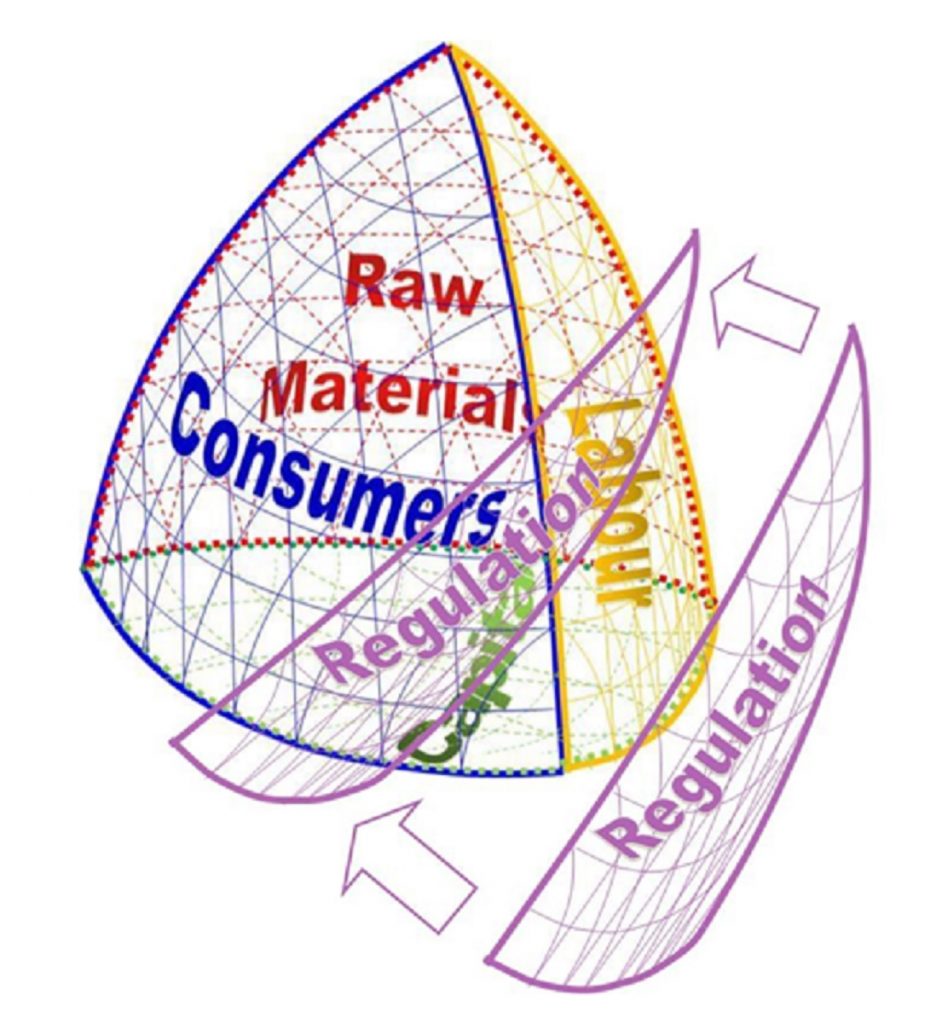

Diane Coyle starts in much the same place as other economists who look at limits of markets and the place of government intervention in markets. She starts with conventional analysis of market failures, listing seven instances of failure in the conditions required for free markets to be efficient. She returns these seven types of failure throughout her examination of the relationship between markets, the state and people, and description of the appropriateness of state intervention or collective action to address.

In cataloguing the failures and the responses to them, Coyle assists the reader, from the economics or politics undergraduate or MBA student getting their first exposure to welfare economics and public policy, through to the general reader seeking a better understanding of how the world works. She draws on and explains clearly the work of people like Coase, Ostrom and Thaler who have broadened and deepened our understanding of how people both cause and respond to the seven types of failure she describes. The book is furthered enriched, and the lessons consequently rendered more accessible, by a peppering of case studies illustrating the core arguments.

Coyle also tackles government failure, highlighting the shortcomings in bureaucracies (or among public servants) and as a consequence of political failures (or failures of politicians) that result in the application of the wrong policies to address the market failures. The text seems to peter out in the final chapter where she addresses what she appears to hope is the solution to the problems of government failure, which is the application of evidence to economic policy. In this chapter that she reveals the limitations of her experience as a career academic and regulator, with a rather slight addressing of the use of statistics and cost benefit analysis. This doesn’t detract from the power (or readability) of the previous nine chapters, but point to the opportunity for someone else to write something of similar tone and quality to fill the gap on how to test public policy initiatives to address market failure.