Exposure to linear programming while doing my MBA at Stanford informed the model of the firm that I described first in May 1980 in a paper for Steve Brandt’s seminar on strategic management and developed into a core component of the Escondido Framework. So when I was told recently about Robert Dorfman’s “Application of linear programming to the theory of the firm” (Berkeley, 1951) and a collection of essays from a 1958 symposium at the University of Michigan edited by Kenneth E Boulding and W Allen Spivey titled “Linear programming and the theory of the firm” (New York, 1960), I thought I should take a look.

Both titles engage somewhat futilely in trying to extend the application of linear programming beyond its useful limits, and swamp the conceptual opportunity of applying a way of thinking about organisational problems with multiple constraints with the desire to created mathematical analytical models under conditions that are necessarily massively complex, non-linear, and dynamic.

Dorfman’s final chapter, on “Assumptions, Limitations, and Possibilities” highlights the limitations of the techniques that he explored in the previous chapters, particularly in relation to the static conditions under which the analysis might be undertaken, the challenges of coping with a dynamic and multi period condition, and with uncertainty. He effectively gives up: “There is little reason to hope that linear programming, or any other simple formulized technique will be able to comprehend this entire problem”. This probably still applies even in an age of massive computing power and ability to capture and interrogate “big data” that Dorfman could never have imagined. He did acknowledge that at the time of writing his book that “linear programming emphasises the physical inter-relationships of productive processes almost to the exclusion of the demand side”. My memory of studying linear programming at the Stanford Graduate School of Business in 1979 is that in this respect at least the commercial applications of linear programming had moved on the in following few decades. Ultimately, however, Dorfman retreats back into an assumption that linear programming could be best applied to managing and optimising internal processes, accepts that the practical applications will be limited in the short term, but remained hopeful, that “economists can rely on the mathematicians, the electronicists, and the statisticians to provide a practical tool.”

The final two essays in Boulding and Spivey’s collection move beyond the descriptions in the earlier essays of the mathematics of linear programming and how they might be applied to the activities of the firm. Interestingly in the context of a book about the application of linear programming, both end up focussing on the difficulty defining the objective function for the firm, arguing that firms seek to more than just maximise profits.

C.Michael White’s essay “Multiple Goals in the Theory of the Firm” reviews the thinking prevailing at the time about the various goals for the firm, both within the scope of profit maximisation (eg in relation to time horizons, to strategic considerations such as discouraging competitive market entry, and in relation to public relations). He cites AG Papandreou, suggesting that he had pointed out that “profit is simply one possible ranking criterion in a broader system of preference-function maximisation. Under perfect competition, profit is the only ranking criterion consistent with survival. In the absence of perfect competition the long-run survival of the a firm may be achieved best (or at least as well) through the maximisation of goals other than profit.”

White addresses the issue of the survival of the firm “The firm as a social and economic organization, like many other organisms, has a compelling urge to survive. More fundamental than the profit motive, the motive to survive is implicit in most decisions within the firm, though the possibility of organizational suicide should not be ruled out”. He later observes “Survival, including the consequent homeostasis concept (Boulding, Reconstruction of Economics, New York, 1950) is seldom an explicit primary goal of a firm but instead provide a pervasive set of limitations on other goals including profit.” However, White fails, surprisingly in an essay in a book about linear programming to close the loop that is embedded in the Escondido Framework model of the organisation as the occupying the virtual space bounded by its market interfaces with customers, capital, labour, other suppliers etc. But he goes some way in this direction, for example identifying later in the paper that “In most instances financial objective are evidenced as additional constraints on other objectives.

White’s summary is as good a description of the objective of the firm as any I have come across since embarking on this project in 1980: “The goals of firms represent a wide array of alternative objectives of which profit maximization is only one, although without doubt a most significant one. In those instances where firms strive to maximize profit all other aspects of the firm’s behaviour impose restrictions on this goal.” (He continues his summary by observing “The difficulty of estimating with accuracy the long-run prospects of a firm makes survival or homeostasis (when interpreted as a relative position within an environment) the most likely long-run objective.”)

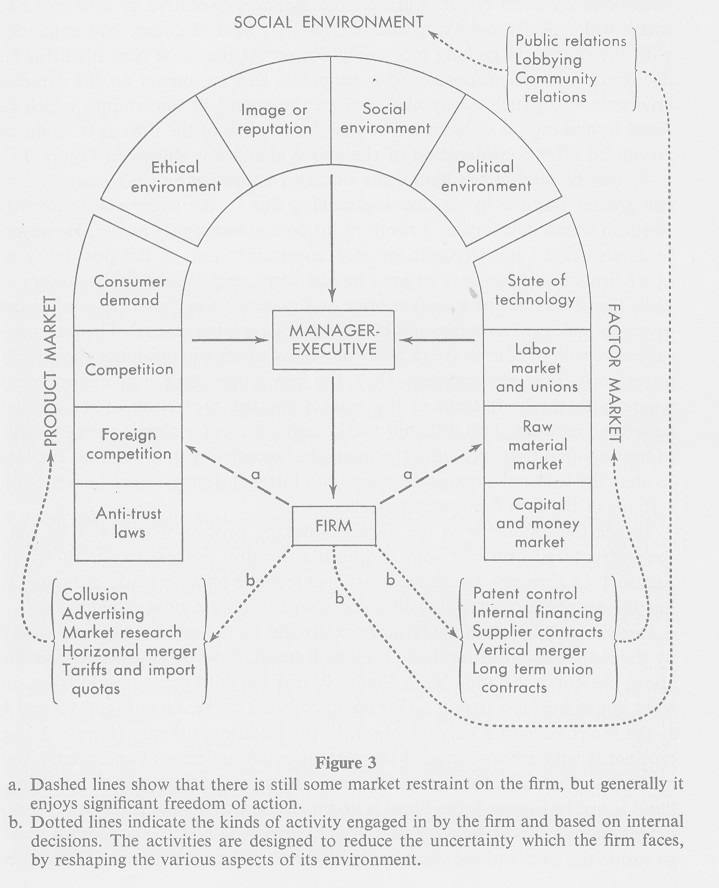

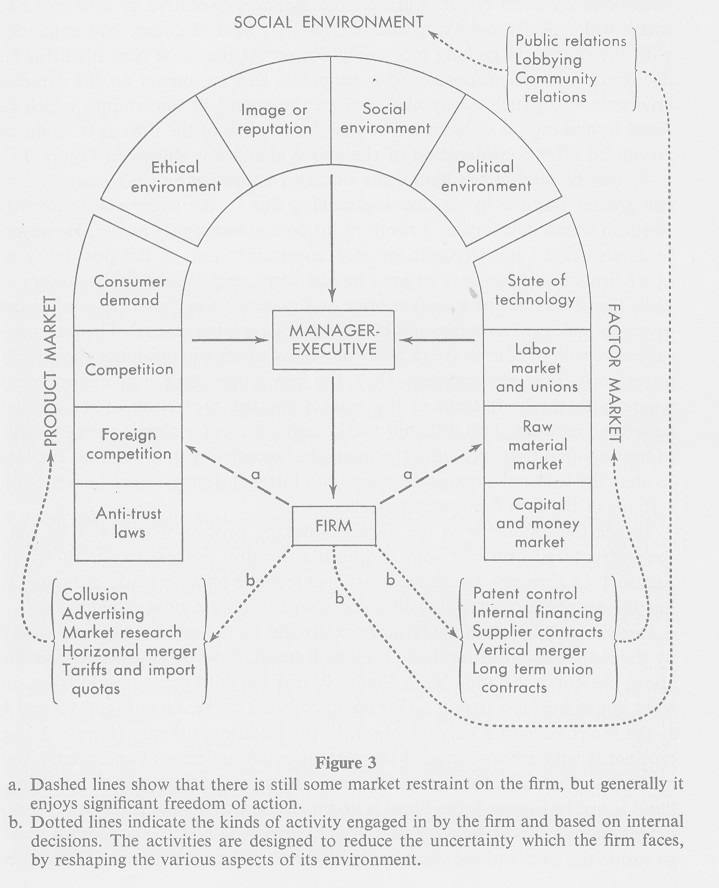

Sherrill Cleland’s “A Short Essay of a Managerial Theory of the Firm” is an insightful attempt to move beyond what he describes as “the Traditional Firm”, a limited model developed from the work of Marshall, Chamberlin and Robinson in the 1930s and 1940s essentially seeing the firm as a passive respondent to conditions imposed by external markets for consumption, capital, labour, and materials, and the competitive industry structure. He describes how while economists were studying the operation of the market to understand the allocation process, businessmen were “developing a strong propensity to innovate in order to gain temporary monopoly control over market forces. As the businessman learned by doing, his propensity to innovate shifted to a propensity to monopolize and temporary monopoly became more permanent. The pattern of internal decision-making which he followed was designed to minimize the external constraints which had theoretically limited his decision alternatives. The initial managerial revolution, then, was an attempt by the businessman to control or influence the external forces (the product market and the factor market) that had been controlling and limiting him. That he was successful, and patently so, is evidenced by our antitrust laws. He wished to expand his field of choice, his set of alternatives, while simultaneously reducing the degree of uncertainty he faced.” He captures the different types of relationship with these external forces in the following figure, that distinguishes between those that the business accepts as given, those that provide a degree of restraint but are subject to influence, and the activities that the firm can reshape in response to its own decisions.

Cleland later proceeds develop his “Managerial Theory”, reflecting how the firm, operating in imperfect markets and consequently with options in terms of pricing and other parameters, is in a position to take choices about its internal operations, processes and outputs, and consequently is able to consider goals other than straightforward profit maximisation. He considers the possibility of satisficing behaviour, for example ensuring only that profit levels exceed the cost of capital and perhaps share the benefits of market power through spending on social responsibility programmes, and also minimax behaviour, for example by engaging in defensive pricing to secure long term contracts and thereby reduce uncertainty or discourage competitive entry.

Cleland further explores how decisions are made within the firm, and highlights to failure of traditional economic models of the firm to consider the role of the people within the firm, in particular the “manager-executive” in taking decisions, and in turn the way that the institutionalised processes, policies and procedures shape the way that decisions are taken, and the decision themselves. He also examines the firm as an information system, with flows both up and down the organisation, to provide the basis for decision-taking by managers and their execution of these decisions by subordinates.

In common with Dorfman, Cleland hopes that his essay is merely laying the foundations for further work, but I have been unable to establish whether he undertook further work in this field or whether this essay provided the foundation for the work of others. Nonetheless, a sentence in his closing paragraph about his “Managerial Theory” that deserves wider airing for its emphasis on “satisfactory profit” and the decision-making power of management: “The managerial theory of the firm considers the firm as an organized information system, intent upon a satisfactory profit level operating in an external and internal environment which allows the manager significant decision-making power.”