The BBC World Service is the insomniac’s salvation. If you are lucky, a background of talk radio helps you back to sleep. If you are luckier still, you stumble on a piece of quality programming that Auntie has chosen to share with the rest of the globe but not with its domestic listeners.

“In the Balance”, a business programme presented by Andy Walker at 03:30 GMT on Sunday 2nd November, included a first class discussion of short termism between Bridget Rosewell, Geoffrey Franklin and Richard Dodds, following an interview with John Kay that marked the second anniversary of the publication of his report for HM Government on short termism in equity markets.¹

The essential conclusion of the Kay report [reference needed] was that there is too much short termism in UK corporate life at the expense of addressing long term competitive advantage. The top management of quoted companies focus unduly on hitting 3 monthly targets, which are a poor measure of management competence, and have been rewarded accordingly. The 1990s featured attempts to align management incentives with the interests of shareholders, but the net result was that “many people who were quite incompetent made quite a lot of money”. Kay concludes that regulation is not the solution, but that a change in culture is required, but that it is hard to know how to do this, and harder still to measure progress.

Kay expanded on the culture change required and the inherent difficulties. He referred to the “marshmallow test”, an experiment with 4 year old children. Most, when presented with a marshmallow and told that if they wait 5 minutes before eating it they will be given a second one, will eat it right away. (A celebrated study of children subjected to the marshmallow found that those who exhibited a lower personal discount rate and exercised sufficient self control to win the second marshmallow – or maybe just had the insight to understand the challenge facing them – prospered more in later life). Andy Walker asked John Kay whether he was saying that executives simply need to grow up, to which Kay responded “a lot of company directors would fail the marshmallow test.”

In the ensuing discussion among the panellists, Bridget Rosewell blamed her profession (economists) for promulgating the view that all the information about the future prospects of the company is captured in the share price, and consequently many board level remuneration packages have been structured around movements in the share price, and the panel as a whole seemed to conclude that we have spent years telling people to focus on the wrong thing. Further, Rosewell also observed that “All markets exist in institutional contexts and cultural contexts.”

Is John Kay right? Undoubtedly yes. But the supplementary questions are more interesting: why do so many fail the marshmallow test; and what can we do about it?

There are probably could be three underlying reasons for the behaviour Kay describes.

One is that, notwithstanding the experimental data that suggests that people who come out on top in later life are those who as small children passed the marshmallow test, perhaps some of those who make it to the upper reaches of commercial organisations respond disproportionately to short term signals. (Or maybe, by the time that they have reached the upper reaches they are no longer capable or responding to anything other than short term signals?). This is not something that I have observed myself, but there may be some revealing academic research lurking in the nether regions of a business school somewhere that addresses the personality types of chief executives and points to this failing.

A second explanation could be that human timeframes and organisational timeframes may be intrinsically misaligned. “In the long run, we are all dead.” The career time horizon for a typical chief is only exceptionally longer than twenty years on first appointment. Even then, the time horizon within the specific appointment is only exceptionally more than ten – and probably for very healthy reasons including personal boredom thresholds and the benefit from time to time for a fresh set of eyes on a problem. Whether it is desirable is irrelevant, it is entirely reasonable for individuals to consider the rewards – both material and emotional – that will flow from what is deliverable and measurable within their own term of office. And although they may also be concerned for their own legacy in the role, they also have to reflect that they have little power to stop those who come after them frittering it away.

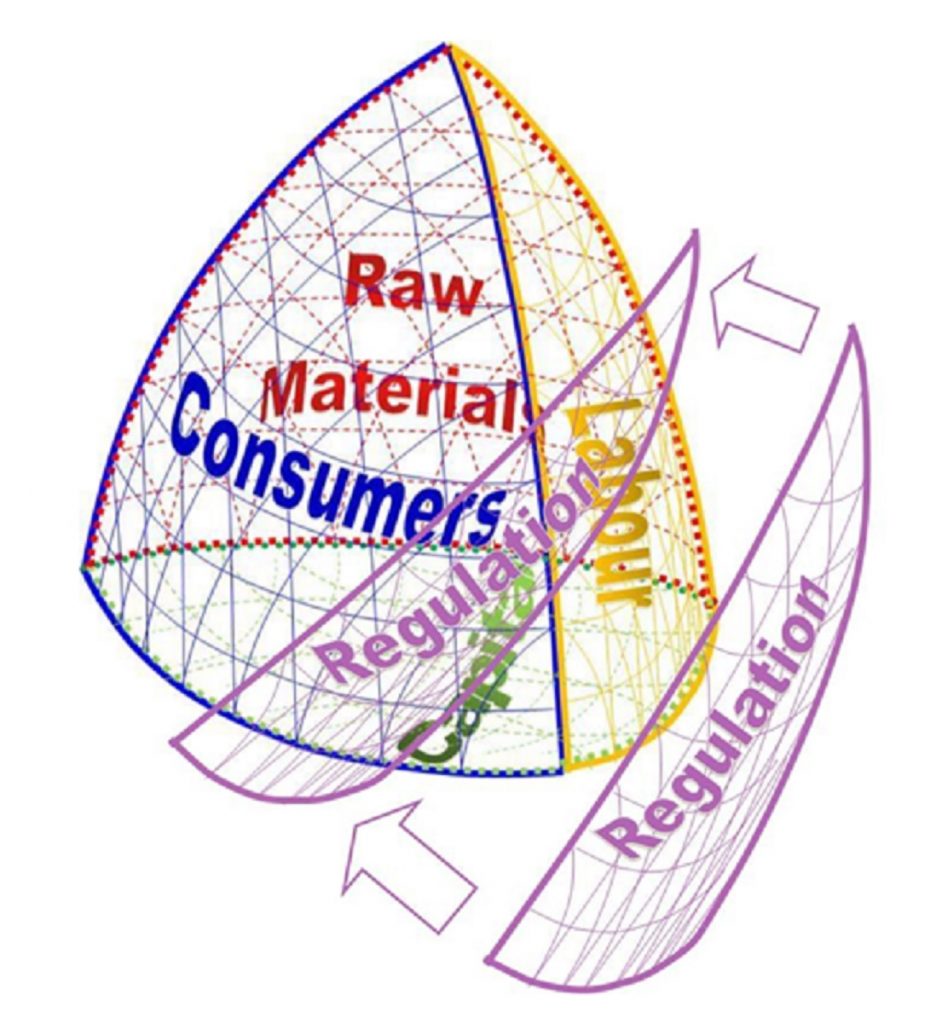

The final explanation relates to the institutional and cultural frameworks about which Kay and the “In the Balance” panellists agonised. The evidence here is compelling (although I would not go as far as Rosewell in condemning the argument that share prices capture all the information about a company – the point, for discussion in more depth elsewhere, is that the prices of traded financial instruments are corrupted because they also capture information about expectations about trader behaviour (in an economist’s version of Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle). Many management teams have been presented by academics, consultants, brokers, investment bankers, and journalists, arguably in error, that they must respond to and seek to affect short term share price performance, and the regulator environment has encouraged rather than discouraged this. Given that the possibility that the first of these three explanations holds true for some executives, and the probability that the second of these three explanations holds true for most, it is all the more pernicious that the we have aligned cultural and institutional frameworks in this way. Instead, we need to bend over backwards to create a culture and institutional framework as a counterweight to the possibility that personal discount rates – driven by hardwired human appetites and instincts – are higher than those of companies and organisations in general, and society overall.

So, who’s eaten my marshmallow?

¹ The Kay Review of Equity Markets and Long Term Decision Making, July 2012