Latest

Worker representation on boards: not exactly a U turn…..

….. but a sensible course adjustment to avoid the rocks.

The FT reports this morning that “Ministers are looking at ways to water down Theresa May’s pledge to put workers on company boards by exploring more practical options that do not run the risk of holding back day-to-day business operations”. This specific part of the report can hardly be fresh news, since doubts were expressed in many circles, not just in this blog, about the practicality of the proposal and whether it would achieve the desired outcomes. But clearly the spin doctors have now decided that it is time to prepare the ground for a course adjustment.

After reporting on reservations held by Greg Clark and Philip Hammond, the FT article continues by commenting that “when asked about the proposals, Downing Street was less definitive about the exact form that worker representation would take….According to one aide, the detail has been difficult to negotiate….admitting that there has been ‘some disagreement’ within cabinet”.

The challenge facing Mrs May – who set out her commitment unambiguously and in identical words on two occasions, following her appointment and then at the Conservative Party conference – is how to avoid providing her critics with yet more evidence of flip flopping on policy. The FT reports “Another aide said that it was not the specific detail that mattered as long as the policy sounded reasonably similar to the original promise.”

There is a solution, described here after Mrs May repeated her commitment to worker representation at her party’s conference on 5th October, that addresses the criticisms of the proposal that it faced after she first made the commitment in July (25 July post).

“So what should she do? There is a way for her to secure representation of worker interests on boards without appointing worker representatives. Submitting the appointment of all directors to a vote of all employees, in the same way that they are subject to approval in a shareholder ballot, would demonstrate an equality between shareholders and employees. In practical terms, it would force chairmen, nomination committees and large shareholders to consider the balance within the board, demonstrate that the slate of directors represent the interests of the company as a whole, and avoid the nomination of directors to whom the label “toxic” could be attached and whose inclusion could result in rejection in the employee ballot.”

The Uber employment tribunal decision through the prism of the Escondido Framework

How does the Escondido Framework interpret the impact of the decision of an employment tribunal in London that Uber drivers are not self-employed?

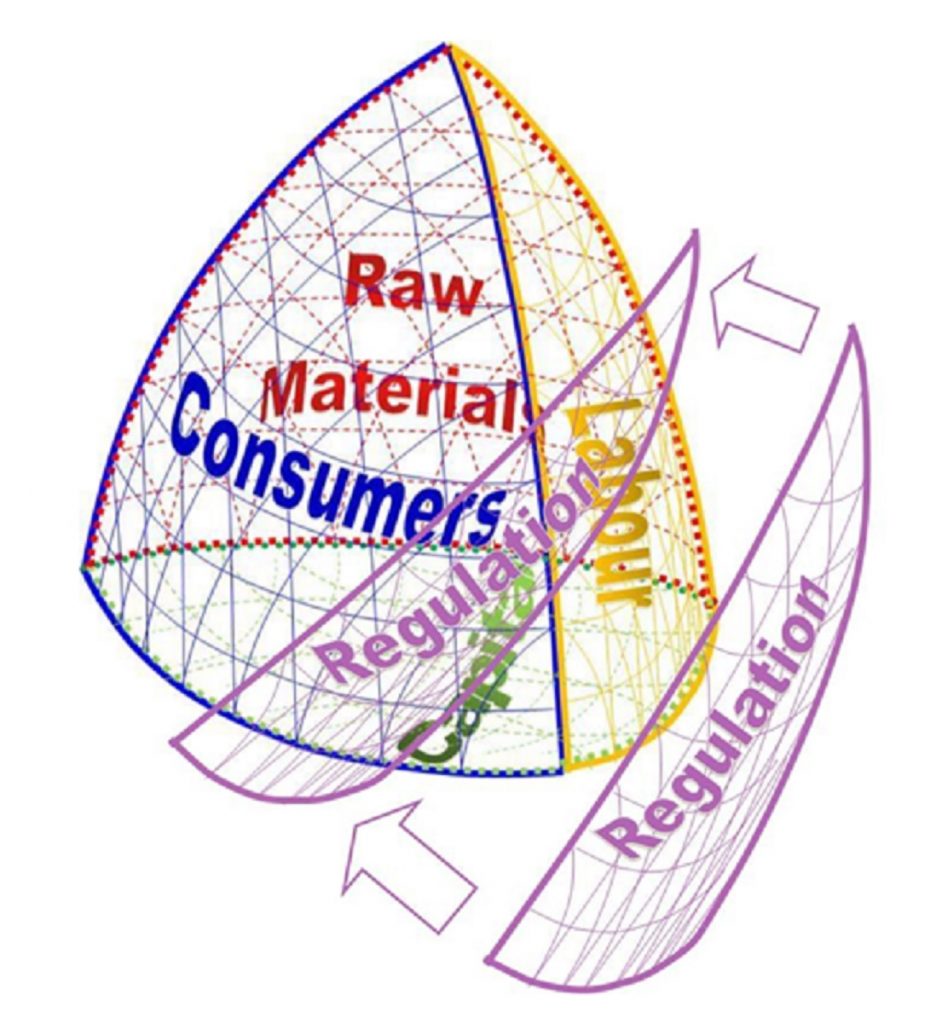

The Escondido Framework describes an organisation as both the solution space that exists between the external interfaces, or markets, and the structure, systems and processes within the solution space that mean that it creates value above and beyond what would exist in the absence of the organisation.

The first consequence of the employment tribunal was to address as matter of law as opposed to economics what Uber buys and sells. Uber hitherto has maintained that it provides a platform that brings together drivers and passengers – ie it provides a service that facilitates the provision of rides by self employed drivers to would be passengers who log on to the platform – rather it provides a transport solution to passengers using drivers that it employs. The judgement challenges the first model by effectively establishing that framework of the contract between the Uber and its drivers means that are being treated as though they were employees rather than self employed at arms length by the company.

The Escondido Framework is helpful in understanding how a judgement by lawyers considering employment lawyer can apparently transform the relationship between an Uber driver and Uber. Uber describes a relationship with the driver that makes them a customer of the company – a self-employed person who pays 25% of the fare secured to Uber in recognition of his or her use of the Uber platform. The Employment Tribunal found that, because of the constraints on the driver under the contractual relationship with company, the Uber driver is a supplier of labour – “an employee” – a factor of production in the provision of a minicab service by Uber to passengers.

The Escondido Framework is essentially neutral between the parties to a transaction: each is a customer of the other and is subject to terms that agreed in a contract of one sort or another, either explicit or implicit. Uber has certainly created value in creating and operating the platform, and thereby has created an organisation that occupies a virtual space bounded by market interfaces with drivers and passengers. Other interfaces bounding Uber’s virtual space include: those with its other employees – programmers and software engineers for example[1]; with its investors; and, as illustrated by this dispute and others with city transport authorities that license taxis, with the political and legal interfaces.

Given the restrictions on drivers, meaning that they cannot simultaneously be attached to multiple platforms, and that the passenger, although able to make choices among available drivers and vehicle classes, has relatively little ability to discriminate between drivers (I see a considerable contrast between Uber and other internet platform businesses such as eBay in this regards) it is hard to see Uber as a company selling a platform to users as opposed to selling journeys to passengers with drivers as employed labour, or at the very least suppliers that allow it to provide those journeys. In this interpretation, Uber is a very conventional organisation providing taxi services, with a highly efficient and well developed set of systems and processes that has created a lot of value, and in Escondido Framework language “solution space”, between the market interfaces of supplier/labour and customer.

Visualising the organisation within the Escondido Framework, in its most simple form as a Reuleaux Tetrahedron, one interpretation of the employment tribunal decision for Uber is that the interface with the labour market has moved and changed in shape. Alternatively, the judgement could be interpreted as a movement of the interface with the regulatory and political market place that reduces the solution space by limiting the parts of the labour market interface that are available to Uber (ie the self employment part of the interface is no longer available to it).

The outcome is indisputable. The solution space available to Uber is smaller, with a consequence that the latitude in terms of strategy available to its management is reduced, along with the amount of economic available for capture by the management and any other interested parties being reduced.

But assessing which of the market interfaces has changed to reduce the size of the solution space is more complex. Is it that the consequence of the legal judgement is that drivers will no longer be willing – as a consequence of the protection of rights arising from the employment tribunal decision – to work on the mix terms that they would previously have accepted? If so, this would represent a change in the position and shape of the market interface. Or is it that the market interface – which is collection of points representing an acceptable mix of terms of “employment” to drivers (payment, sick pay, holiday pay, employer imposed restrictions on availability, ability to take other work, ability to turn down rides, access to tips from passengers, discretion about routes to take, condition of the car that they driver must maintain etc) has not changed, but that the movement of the interface with the political and regulatory world (the market for political influence, which in Uber’s case may well have been influenced by other aspects of the company’s conduct), has moved in way that has removed some of these points from being available (see illustration below)

[1] Subsequent to this post some very interesting issues arose surrounding the way that Uber has positioned itself against this market interface, giving rise to repeated charges of sexism and sexual discrimination

Three Faces of Power, Kenneth E Boulding 1989

The great thing about Amazon is how easy and inexpensive it is to track down potentially interesting texts referenced in footnotes. The outlay of 1p plus £2.70 post and packaging secured the arrival of a copy of Kenneth E Boulding’s “Three Faces of Power”. This arrived virtually in mint condition other than a barcode and a stamps indicating that it been discarded from the library of the Ecole Superieur de Commerce de Paris – and certainly with little evidence that it received much attention from the ESCP’s students.

Published in 1989, it addresses – albeit from a different angle – the three currencies that have since the early 1980s been among the core elements of the Escondido Framework. The publisher’s blurb on the back cover claims that Boulding’s “creative analysis lays the groundwork for important future debates about power.” I have been scratching around for this sort of stuff – albeit as hobbyist rather than academic – since leaving Stanford in the summer of 1980. The fact that it has taken me so long to come across this work and that it, in turn, appears to have sunk almost without trace, reminds me of T S Eliot’s lament:

“And what there is to conquer

By strength and submission, has already been discovered

Once or twice, or several times, by men whom one cannot hope

To emulate—but there is no competition—

There is only the fight to recover what has been lost

And found and lost again and again”

(from East Coker, No 2 of The Four Quartets, T S Eliot)

Boulding divides power into three major categories: “threat power”, destructive in nature and applied particularly to political life; “economic power”, resting largely on the power to produce and exchange items, and on the constantly changing distribution of property ownership; and “integrative power”, based on such relationships as legitimacy, respect, affection, community and identity. These three categories do not map directly onto the three currencies within the Escondido Framework, but Boulding himself accepts that they are what mathematicians call “fuzzy sets”. However, there is a rough approximation for “threat power” to the approach to transacting using the “force” currency. It is easy to see how Boulding’s “economic power” maps onto the approach transacting using the “cash” currency. Unsurprisingly, his “integrative power most closely relates to the “influence” currency of the Escondido Framework.

Right diagnosis, wrong prescription: Theresa May’s worker representation proposal

Just in case we weren’t listening in when she talked about worker representation on boards on becoming prime minister in July, Theresa May used exactly the same words (highlighted in the speech extract below) in her leader’s speech at the Conservative Party conference today:

Too often the people who are supposed to hold big business accountable are drawn from the same, narrow social and professional circles as the executive team.

And too often the scrutiny they provide is not good enough.

A change has got to come.

So later this year we will publish our plans to have not just consumers represented on company boards, but workers as well.

The risk when you same something exactly the same way twice is that you leave yourself without any wriggle room.

Her diagnosis isn’t too wide of the mark but the rush to the particular prescription suggests very shallow intellectual foundations. Mrs May’s proposal for worker and consumer representation on boards has already been challenged on the basis that it conflicts directly with the principle of the unitary board adopted in the UK, which means that all members of the board have the same responsibility for the interests of company – currently defined very broadly under section 172 of the 2006 Companies Act. Individuals appointed by whatever method (and this in itself is a potential source of contention) would inevitably face conflicts of interest between their responsibility to their constituency and to the wider interest of the company and the resolution of the interests of all its “stakeholders”.

However, it is good that Mrs May is committed to rebalancing the interests of the various parties – particularly workers and customers (but by extension surely she would include suppliers, certainly in the grocery industry) – with shareholders, and containing executive pay. I fear that the prime minister herself lacks both the appetite and opportunity to engage with a new intellectual model of the firm to help her decide how best to reform corporate governance. We can only hope that she is willing to instruct her advisors to seek out frameworks to provide a solid platform for reform. With such a framework, there is a great deal that can be delivered by soft power – exhortation and challenge from No 10 to change behaviour on boards, among the institutional investors few of whom have chosen to use the power they possess, and in the commentariat of academics and journalists.

There is currently an enormous risk that we will have reforms that either deliver unintended consequences or are ineffective. Brexit will clearly consume a vast amount of government attention and parliamentary time, but by repeating the commitment quite so explicitly, the prime minister was not flying a kite but making a commitment.

So what should she do? There is a way for her to secure representation of worker interests on boards without appointing worker representatives. Submitting the appointment of all directors to a vote of all employees, in the same way that they are subject to approval in a shareholder ballot, would demonstrate an equality between shareholders and employees. In practical terms, it would force chairmen, nomination committees and large shareholders to consider the balance within the board, demonstrate that the slate of directors represent the interests of the company as a whole, and avoid the nomination of directors to whom the label “toxic” could be attached and whose inclusion could result in rejection in the employee ballot.

Paul Polman, CEO of Unilever, on sustainability, purpose and living by his values

In the late 1980s, the buying and merchandising team I led at high street retail chain WHSmith launched a substantial new range of environmentally responsible stationery. It resonated with the personal values of the team, in short we believed that it was the right thing to do. We also argued that it would be good for the company and provide us with an edge over competitors, since it would be attractive to a significant number of our customers, would help us with staff recruitment since we believed that smart young people wanted to work for an environmentally responsible company, and would help enhance the wider reputation of the company with marketing benefits spilling over into other product categories and win sympathy for us in other ways, even to the extent, for example, of creating a benign audience in local authority planning decisions.

This weekend’s FT contains a profile of Paul Polman, chief executive at Unilever for the past seven years, who has taken an even bolder and more extensive approach to environmental responsibility. His leadership reflects an explicitly understanding of the diversity of market dimensions and that companies need to consider, a sense of that the purpose of the company reflects long term sustainability – of the company and the environment in which it operates.

His responses to his FT interviewers speak for themselves:

“P&G started in 1837, Nestlé in 1857. These companies have been around for so long because they are in tune with society. They are very responsible companies, despite the challenges that they sometimes deal with, all the criticism they get”

When Polman became chief executive of Unilever …. he said that he only wanted investors who shared his view that Unilever needed to shepherd the Earth’s future as carefully as it did its own revenues and profits…..“Unilever has been around for 100-plus years. We want to be around for several hundred more years. So if you buy into this long-term value-creation model, which is equitable, which is shared, which is sustainable, then come and invest with us. If you don’t buy into this, I respect you as a human being but don’t put your money in our company.”

The FT article explains that Sustainable Living Plan adopted by Unilever has not met all its targets, pushing back the date for halving its products’ environmental impact from 2020 to 2030 but it has reduced the waste associated with the disposal of its products by 29 per cent, with the aim of hitting 50 per cent by 2020. It is not without its critics, but a report from Oxfam report on the company’s practices in Vietnam identified “a number of critical challenges in translating the company’s policy commitments into practice”, the charity’s latest Behind the Brands ranking, which looks at the top 10 food companies’ record on small farmers, women’s rights, the use of land and water and greenhouse emissions, put Unilever in first place, ahead of other leading consumer products companies.

The outcome has been good for the company’s relationships with investors. In the FT’s words: “while he told short-term shareholders to shove off, he delivered good returns to those who stayed. Unilever’s total shareholder return during Polman’s tenure has been 203 per cent, ahead of his old employer Nestlé and well ahead of P&G………. The company has also succeeded in attracting more long-term shareholders………before Polman’s reign, 60 per cent of the company’s top 10 shareholders had been there for five years or more. Today, 70 per cent have held their shares for more than seven years.”

It is also clear from the FT article that Polman has also adopted this approach to environmental sustainability because of its alignment with his personal beliefs, and that his belief that the wider purpose of the company (which he likes to an NGO) is a further illustration of his own belief that he should live his personal values in his corporate career. The Saïd Business School’s Colin Mayer, author of The Firm Commitment, tells the FT “He has demonstrated immense courage and vision in promoting a concept of the purpose and function of business that initially met with considerable resistance, bordering on hostility, from several quarters.”

Lessons from the misfortunes of Deutsche Bank and Twitter

“John Gapper has written today in the Financial Times about the problems facing Deutsche Bank and Twitter, very different companies but both coincidentally valued at about $16 billion and, but for different reasons, facing an uncertain future. He describes them as both lost in the past and argues that “unless a company finds a way to diversify and expand beyond its core business, it gets stuck”. He makes a good case for the first part of his diagnosis. The second, while well argued about the particular positions of Deutsche Bank and Twitter is far from true as a generalisation in that the both the commercial and non-commercial worlds are full of organisations that have thrived and survived without either diversify or expanding, but who have at least adapted.

The point he makes about Deutsche Bank concerns failed diversification and poorly conceived and executed expansion. He writes: “The obvious lesson from Deutsche’s experience is not to lose touch with your roots. “It strikes me that a lot of banks have lost a sense of what made them special in the first place,” says Chris Zook, a partner of Bain & Company, the management consultancy. The bank’s corporate business is outweighed by retail banking and securities trading, neither of which is doing well….. From early on, Deutsche decided that its founding mission — to challenge the hegemony of UK banks in financing foreign trade in the late 19th century — was too small a niche. But expanding into retail and small business banking, as it did after being reconstructed in 1957, was tricky.”

He describes the problem of Twitter as being a victim of the niche in which it was conceived, the 140 character SMS defined tweet, that now is on the slide and any enhancements are proving insufficient to cope with competition. He contrasts this niche definition at conception with the vision of Jeff Bezos who: “astutely started a business that was neatly defined yet had equally clear room to grow. He entrenched it in the public’s mind as an online bookseller before expanding into other products”. Gapper is conveniently ignoring Amazon’s first mover advantage. It is hard to remember now, but it was founded in the earliest days of the world wide web, in 1994, whereas Twitter only came into existence in 2006, when the internet was much further evolved and Facebook, for example, was already two years old.

Gapper contrasts Twitter with Facebook pointing out that it was restricted when first launched, with strict rules about who could befriend users, but Mark Zuckerberg was able to widen its scope by adding videos and messaging relatively early and with a strong revenue model that allowed him to generate both investment and cash that allowed him to buy businesses like Instagram and WhatsApp to neutralise competition both by taking competitors out an enhancing the core service offering.

So what does Gapper think will happen next to these two: “Deutsche now wants to turn back to something closer to its origins, rebalancing towards corporate finance and asset management with less of the expensive grandeur of investment banking. Twitter seems more likely to take shelter within a bigger company”. This first option appears doable, and actually gives the lie to Gapper’s opening argument about diversification and expansion and, if not “sticking to the knitting” is returning to the knitting. In Twitter’s case, it appears that the only hope is finding another company who can replace the company’s interface with the external financial market with a hierarchical relationship to a group HQ and, if there are indeed value creating opportunities for a new parent, something that provides enough sustainable value in the broadcastable message of less 140 characters and audiences that seem fickle and ephemeral to justify an price that provides some sort of return to the existing shareholders.

Footnote: Gillian Tett reports in FT 30th September that Deutsche Bank paid staff 4bn euros in bonuses in 2006 and 2007 and 2bn in 2008.

Highlights from October 2016 Harvard Business Review

My two picks from the latest Harvard Business Review relate to two Escondido Framework themes: the way that executive teams have been the beneficiaries of the misunderstanding by shareholders (or, rather, their representatives on remuneration committees) of what motivates them and how the relevant market relationships work; and the need to think about employees as customers.

An article titled “Compensation, the case against long-term incentive plans” reviews the work of Alexander Pepper, set out in his book “The Economic Psychology of of Incentives: New Design Principles for Executive Pay (Palgrave Macmillan 2015). Pepper documents how pay for performance incentives, and Long Term Incentive Plans in particular, fail to work as proponents expected. The four reasons are summarised as follows:

- Executive are more risk-averse than financial theory suggests

- Executives discount heavily for time

- Executives care more about relative pay

- Pay packages undervalue intrinsic motivation

HBR’s review of Pepper’s work, in its Idea Watch section, comes not long after news broke in London on 22nd August that Woodford Investment Management was to scrap all staff bonuses, based on the belief that ‘bonuses are largely ineffective in influencing the right behaviours.’

The second article of interest is an article by Cheryl Bachelder, CEO of fast food franchise Popeyes: “How I did it…… The CEO of Popeyes on treating franchisees as the most important customers”. It’s not so much the lesson expressed in the article’s title that excites me, but an extract in the middle of the text that takes the message a stage further, recognising staff as customers:

At one point in my career, I was touring restaurants to talk to team members about the importance of serving guests well. I met a young man who was not excited about my “lesson”. He asked who I was. “I’m Cheryl,” I said. “Well Cheryl,” he said, “there’s no place for me to hang up my coat in this restaurant, and until you think I’m important enough to have a hook where I can hang up my coat, I can’t get excited about your new guest experience program.” It was a crucial reminder that we are in service to others – they are not in service to us.

How to build a business that last 100 years?

The Boston Consulting Group’s latest BCG Perspectives brings a TED talk from one of its partners, Martin Reeves, titled “How to build a business that last 100 years”. His thesis is that we should look to lessons from biology to create lasting businesses. He links the failure of businesses to survive – pointing out that the average US public company has a life of only thirty years and probability that any public US company will still be around in five years’ time is only 32% – to a “collapse of the corporate immune system”.

He explains that human immune system, and indeed all successful biological systems from forests to fisheries, and indeed such long lasting social systems as the Roman Empire and the Catholic Church, display six characteristics:

- redundancy (“millions of copies of each component — leukocytes, white blood cells – a massive buffer against the unexpected”),

- diversity (“not just leukocytes but B cells, T cells, natural killer cells, antibodies”),

- modularity (“the surface barrier of the human skin….the very rapidly reacting innate immune system…..the highly targeted adaptive immune system……if one system fails, another can take over”),

- adaptivity (“able to actually develop targeted antibodies to threats that it’s never even met before”),

- prudence (“detecting and reacting to every tiny threat, and furthermore, remembering every previous threat, in case they are ever encountered again”),

- embeddedness (“in the larger system of the human body, and it works in complete harmony with that system, to create this unprecedented level of biological protection…… if one system fails, another can take over, creating a virtually foolproof system”).

He explains that along with and as a consequence of these characteristics, biological systems are complex and can seem inefficient, in contrast to the instincts of most managers and what is taught in business schools and preached by consultants.

Reeves continues by applying these lessons to examples of corporate failure. His first is the tragic loss of independence of Kongō Gumi, builder of Japanese temples for 1,428 years and managed by members of a single family until it forgot the principle of prudence, borrowed heavily to finance real estate purchases in the 1980s and was finally liquidated in 2006 and its assets sold to a large construction company.

Shitennoji Temple, built by Kongō Gumi (578-2006)

He then contrasts the collapse of Kodak with the successful adaptation of Fujifilm, which used its capabilities in chemistry, material science and optics to allow it to diversify into sectors outside photographic film, surviving “because it applied the principles of prudence, diversity and adaptation”. He also cites the success of Toyota in surviving a devastating fire in the only plant which supplied it with valves for car-braking systems. He describes Toyota’s ability to work collaboratively with its suppliers to repurpose production as an application of “the principles of modularity of its supply network, embeddedness in an integrated system and the functional redundancy”.

I am sure that there is something in Reeves’ argument, but some of it is contrived and overall it would be more compelling if some of the example illustrated his six principles more comprehensively, rather than only illustrating one or two.

Certainly Kongō Gumi’s demise reflects a lack of prudence – but the most extraordinary aspect of the story is that it had survived for as long it did, which may reflect the lack of underlying change in the Japanese temple market over almost a millennium and a half. To quote Business Week’s report on its demise:

“To sum up the lessons of Kongo Gumi’s long tenure and ultimate failure: Pick a stable industry and create flexible succession policies. To avoid a similar demise, evolve as business conditions require, but don’t get carried away with temporary enthusiasms and sacrifice financial stability for what looks like an opportunity. These lessons are somewhat contradictory and paradoxical, to be sure. But if sustained success came easy, then all family businesses would have a 1,428-year run.”

The Fujifilm example illustrates the benefit of diversity in a portfolio, but says nothing about the photographic film enterprise itself. Fujifilm’s survival represents the success of a corporate parent in managing a portfolio (ie the business of managing businesses), protecting the interests of a top management group, but says nothing about the business unit that brought together employees who worked in factories producing film, the customers that constituted the channel to the camera owner, or its suppliers. Essentially, as technology moved on, the “virtual space” between the various market interfaces disappeared and nothing that could be done to protect this enterprise. Its corporate shareholder – the Fujifilm group company – had elected to redeploy the cash flow into other businesses because the ultimate shareholders were either not in a position to, or chose not to, intervene.

Toyota is celebrated for how it manages itself supply chain and the nature of these relationships, but the fact of its ability to bring brake valve production on-line quickly illustrates only three, and possibly only two (given that it explicitly did not have redundancy in its supply chain given that it maintained a single source for these components), of Reeves’ biological system characteristics.

Considering Reeves’ argument and his examples and relating them to the Escondido Framework model of the firm, I certainly concur with three of his principles: adaptivity, prudence and embeddedness. I get redundancy, although not quite as he defines it, but at least that bit of spare capacity, underused resource, or financial headroom. But the need for and appropriateness of modularity and diversity must depend on the circumstances, and sometimes are in conflict.

Timeless themes in Galsworthy’s “Strife” (1909)

My mother in law and I have resolved the problem of the deadweight loss of Christmas (Joel Waldfogel, American Economic Review, December 1993) by giving each other a night out at the theatre, accompanied by her daughter/my wife. Whether last night’s trip to see “Strife” at the Chichester Festival Theatre was her gift to me or mine to her doesn’t matter, it was a great production and my first exposure to John Galsworthy’s insightful exposure of the fallacy of mindless short term focus on shareholder value, the importance of recognising the constraints on the firm of public opinion, and the pressures on the trade union to serve its long term interest over the pressures of the interested parties in the immediate dispute. Furthermore, themes on hand around corporate governance, the tension between external directors and a dominant shareholder chairman, and on the other (in the context of the current junior doctors’ dispute and the tensions within the British Medical Association) between the professional leadership of the trade union and the intransigent leader of the local workers’ committee, have a resonance in 2016 every bit as powerful as they may have had when the play was first performed in 1909.

Wikipedia provides a useful synopsis:

The action takes place on 7 February at the Trenartha Tin Plate Works, on the borders of England and Wales. For several months there has been a strike at the factory.

Act I

The directors, concerned about the damage to the company, hold a board meeting at the home of the manager of the works. Simon Harness, representing the trade union that has withdrawn support for the strike, tells them he will make the men withdraw their excessive demands, and the directors should agree to the union’s demands. David Roberts, leader of the Men’s Committee, tells them he wants the strike to continue until their demands are met, although the men are starving. It is a confrontation between the elderly company chairman John Anthony and Roberts, and neither gives way.

After the meeting, Enid Underwood, daughter of John Anthony and wife of the manager, talks to her father: she is aware of the suffering of the families. Roberts’ wife Annie used to be her maid. She is also worried about the strain of the affair on her father. Henry Tench, company secretary, tells Anthony he may be outvoted by the Board.

Act II, Scene I

Enid visits the Roberts’ cottage, and talks to Annie Roberts, who has a heart condition. When David Roberts comes in, Enid tells him there must be a compromise, and that he should have more pity on his wife; he does not change his position, and he is unmoved by his wife’s concern for the families of the strikers.

Act II, Scene II

In an open space near the factory, a platform has been improvised and Harness, in a speech to the strikers, says they have been ill-advised and they should cut their demands, instead of starving; they should support the Union, who will support them. There are short speeches from two men, who have contrasting opinions. Roberts goes to the platform and, in a long speech, says that the fight is against Capital, “a white-faced, stony-hearted monster”. “Ye have got it on its knees; are ye to give up at the last minute to save your miserable bodies pain?”

When news is brought that his wife has died, Roberts leaves and the meeting peters out.

Act III

In the home of the manager, Enid talks with Edgar Anthony; he is the chairman’s son and one of the directors. She is less sympathetic now towards the men, and, concerned about their father, says Edgar should support him. However Edgar’s sympathies are with the men. They receive the news that Mrs Roberts has died.

The directors’ meeting, already bad-tempered, is affected by the news. Edgar says he would rather resign than go on starving women; the other directors react badly to an opinion put so frankly. John Anthony makes a long speech: insisting they should not give in to the men, he says “There is only one way of treating ‘men’ — with the iron hand. This half-and-half business… has brought all this upon us…. Yield one demand, and they will make it six….”

He puts to the board the motion that the dispute should be placed in the hands of Harness. All the directors are in favour; Anthony alone is not in favour, and he resigns. The Men’s Committee, including Roberts, and Harness come in to receive the result. Roberts repeats his resistance, but on being told the outcome, realizes that he and Anthony have both been thrown over. The agreement is what had been proposed before the strike began.

Missing from the synopsis are some of the more subtle themes in Galsworthy’s text, including the recognition by Harness of the reality facing the company (that it will not survive if the strike continues and the men’s jobs are on the line) irrespective of Roberts’ concern for a wider struggle against “Capital”, John Anthony’s arguments about the primacy of the bottom line and his duty not to compromise, and the concern of the majority of the directors of the company for public opinion (and their personal reputations).