I don’t disagree with Michael Skapinker often, but his commentary on the successful bid by Melrose for GKN in today’s Financial Times “Customers should have come first in the GKN battle” had me getting out a metaphorical red ballpoint to mark his homework.

It was a shame. He made such a good start, rehearsing points that he has made well in the past about shareholder value:

Whose interests should companies serve? For decades, the answer, particularly in the US and the UK, was shareholders’. Total stock market return, the argument went, was clear and measurable and it kept managers focused — until Jack Welch, former General Electric boss and one of shareholder value’s greatest champions, denounced it as “the dumbest idea in the world”.

That was in 2009. Mr Welch was not the only business chief to notice that the financial crisis had shredded the idea that if companies looked after shareholders, everything else would follow. Josef Ackermann, then-head of Deutsche Bank, said: “I no longer believe in the market’s self-healing power.”

A little later in his article, I also awarded him marks for citing the late Sumantra Ghoshal of London Business for arguing in 2005 that:

the people whose contribution should be recognised first were employees, who also took the biggest risks;

shareholders could sell their shares far more easily than most employees could find another job;

and employees’ “contributions of knowledge, skills and entrepreneurship are typically more important than the contributions of capital by shareholders, a pure commodity that is perhaps in excess supply”.

Not content with citing Sumantra Ghoshal with approval, Skapinker moved on later in the article, in the context of the intervention by the Tom Williams, chief operating officer of Airbus’s commercial aircraft division, about the need for long-term investment and strategic vision in the aircraft industry, to cite “the great” Peter Drucker for saying that

the purpose of business was to create a customer. Without that customer, there are no jobs for workers, no returns for shareholders and no strategic skills for nations.

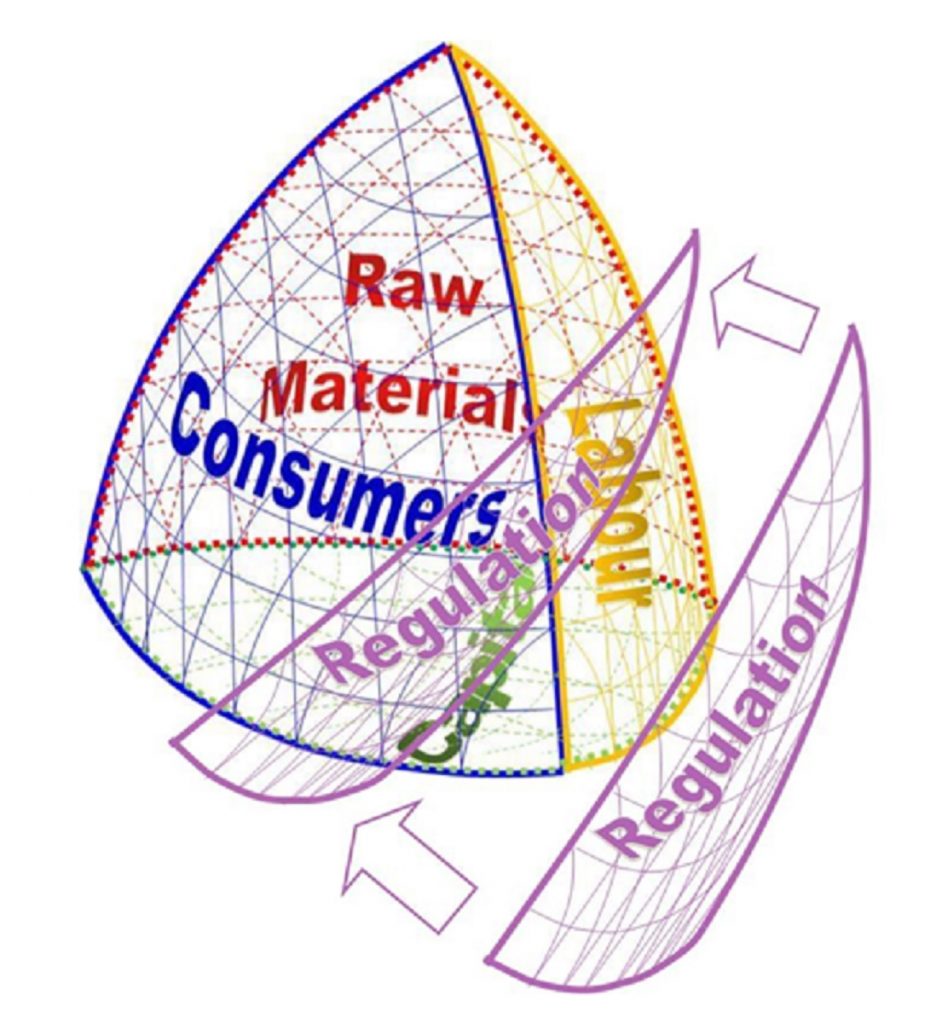

All good stuff, and essentially consistent with Escondido Framework thinking, but Skapinker and others who were unhappy at the outcome of the bid seem to have missed the point about what was happening.

During the takeover battle, much was made of the heritage of GKN, whose origins lay in the founding of the Dowlais Ironworks in the village of Dowlais, Merthyr Tydfil, Wales, by Thomas Lewis and Isaac Wilkinson ion 1759. John Guest (whose name survives in the “G” of GKN – formerly Guest Keen and Nettlefold) was appointed manager of the works in 1767, and in 1786, he was succeeded by his son, Thomas Guest, who formed the Dowlais Iron Company. However, the links to the multinational automotive and aerospace components company of 2018 are slight and accidental.

The company acquired by Melrose consists of four major divisions: GKN Aerospace (Aerostructures; Engine Products; Propulsion Systems); GKN Driveline (Driveshafts; Freight Services; Autostructures; Cylinder liners; Sheepbridge Stokes); GKN Land Systems Power Management; PowerTrain Systems & Services; Wheels and Structures; Stromag); and GKN Powder Metallurgy (Sinter Metals; Hoeganaes). This is a collection of businesses that is the outcome of over a hundred years of acquisitions and disposals across the globe¹. At least at the parent company level, there is little to suggest the opportunity for much value creation from them all being part of the same corporate entity.

What business was GKN plc in? The management of a portfolio of business units, primarily in manufacturing but some in services, spread across a range of different industries and technologies serving a variety of different types and classes of industrial customers, many but not all being OEMs.

Who were the customers of the corporate entity, as opposed to the subsidiaries (which are the entities that interface directly with the purchasers of goods and services, with their employees, and with suppliers)? Perhaps the subsidiaries themselves, insofar that they derived value from the parent company and investment funds, in return for cash returned to the parent? Perhaps the employees of the subsidiaries, at least in so far as they were beneficiaries of a corporately administered pension scheme (that, incidentally, Melrose committed to topping up with an extra £1 billion)?

Much has been made, including by Michael Skapinker in his article, of the 25% of the shares that were in the hands of hedge funds and other short term speculators who had only bought them very recently in the hope of a quick return. Presumably they bought these shares from owners who were willing to sell at a lower price against the possibility that the Melrose bid failed and the share price under the existing management team would fall.

Melrose’s argument during the takeover battle was essentially that it is a management team with a record of successful managing corporate assets who would replace a management team that has been destroying value in its management of the GKN portfolio. The commitments Melrose made along the way to the customers for the GKN subsidiaries’ goods and services and to their employers (in part evidenced by the promises relating to the pension scheme), suggest that they are not old fashioned asset strippers, selling off assets as part of strategy to wind down wealth creating business units. Rather, they appear to understand the business that the GKN plc is currently in, which is managing a portfolio of businesses, adding value to those where it can, and selling those to which other companies can add more value.

If this is indeed the approach that Melrose takes, it will reflect a mindset in which the board thinks about the businesses within the portfolio as customers for the corporate centre, recognising that if there are other corporations that can provide individual business units with a better deal, let them go. And that will make it easier to keep their customers in the capital markets, to whom they have spent the last few months marketing themselves, happy, loyal, and committed.

¹ Wikipedia history of GKN plc since 1966